Thoughts on 'Why Believing in Your Students Matters' by Katie Martin

Today I came across this succinct article by Katie Martin on why believing in our students matters, as this can have a significant impact upon a teacher's practices and students' uptake of learning regardless of where learning and teaching that takes place - whether face-to-face or online.While I have known about the need to wait for responses from students for some time, and I value this approach, sometimes one can wait a bit too long. UK universities have had high and growing numbers of students from China for a while now. Some universities throw their doors open to International students since they pay higher fees.One such university near London where one Master's program of 150+ students has well over 95% of its students from China. At the same time, some of these same universities that seek to recruit large numbers of International students, often heavily reliant upon specific markets such as China, can, at times, lower the bar in terms of language requirements. From my own experience of observing and delivering teaching, this situation, which isn't unique to the aforementioned university, creates a number of issues since the students often:

Today I came across this succinct article by Katie Martin on why believing in our students matters, as this can have a significant impact upon a teacher's practices and students' uptake of learning regardless of where learning and teaching that takes place - whether face-to-face or online.While I have known about the need to wait for responses from students for some time, and I value this approach, sometimes one can wait a bit too long. UK universities have had high and growing numbers of students from China for a while now. Some universities throw their doors open to International students since they pay higher fees.One such university near London where one Master's program of 150+ students has well over 95% of its students from China. At the same time, some of these same universities that seek to recruit large numbers of International students, often heavily reliant upon specific markets such as China, can, at times, lower the bar in terms of language requirements. From my own experience of observing and delivering teaching, this situation, which isn't unique to the aforementioned university, creates a number of issues since the students often:

- come with different levels of language readiness for an intensive postgraduate level of study;

- are not or may not be used to interacting and socializing with those from other countries;

- are unlikely to work outside their 'peer' group of compatriots due to shyness, peer pressure or do so begrudgingly; and/or

- lack confidence in their own abilities and are perhaps not provided with enough motivation from teaching staff to instill a positive, 'can-do' attitude to learning.

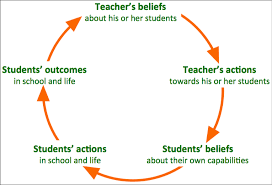

The result of any or a combination of these is that lecturers, academic tutors, learning developers and tutors of English for academic purposes are frequently put into tricky situations: the content has to be delivered, but if students are struggling to understand, what is to be done? Too often I have heard over the years, from staff at various institutions, similar negative remarks that Katie mentions in her article. I've always found these types of comments particularly demotivating and, silently, I ask myself upon hearing sustained negative comments "Well, why the hell are you in teaching?!" It is as if those making such comments were perfect students who always worked hard.On the flip side, the best colleagues I've had have always been positive, supportive and empathetic to the student journey. This empathy seems to set apart the negativity of the moaners from the teachers/lecturers whose lessons that we would always look forward to when we were once students. I think part of this empathy that some educators have is at least partially informed by the works of the Brazilian educationalist Paolo Freire, among others.Going back to Katie's article, I think one solution is creating a positive, welcoming environment that seeks to recognize the students as intelligent participants who are able to interact at Master's level successfully with regular, positive support that seeks to push the students' boundaries and to modify our teaching practices to engage the students in such a way that might tease out from them meaningful participation.One way, I believe, is to have a meaningful, welcoming induction to a program that gets students involved in getting to know their peers and teaching staff beyond the polite formalities of titles and names (think: basic teambuilding activities that get students to solve real problems related to their studies and/or life within their new educational setting). Oftentimes, I've seen inductions that were so superficially boring, stereotypical and/or dry that it immediately set the wrong (superficial) tone for the program of study in question.Another solution is to embed positive thinking throughout a program. As Katie says in her post:

... when we believe we can learn and improve through hard work and effort we can create the conditions and experiences that lead to increased achievement and improved outcomes.

In terms of learning and teaching, this is particularly powerful for our students. If they feel the above, they can and will improve in their learning journey. We, as educators, have a responsibility to instill these ideas into our students, especially International students who might genuinely need extra support, encouragement and motivation in order for them to become independent learners. Part of ensuring the success of our learners is to change our thinking - to think more positively, and to believe in our students.This also means we might need to change our approach to learning and teaching. So, for example, imagine you have a session of 15-50 students and they don't volunteer answers without being called on and prefer to stare at their phone or laptops (or both!). If our students are quiet and reticent to raise their hands to volunteer an answer, then there are some easily-doable solutions.

- Creating regularly-spaced questions to gauge/engage/formatively assess learning can significantly help improve participation, and these can be easily delivered via a response system such as Mentimeter or similar as students only need to use their mobile phone/phablet/tablet/laptop.

- Implementing a Twitter feed so that students can engage during/after a teaching session can also foster learning by using a module/course specific hashtag. These two blog posts have a range of good ideas:

Apart from those small solutions, I believe that part of ensuring the success of our learners is also to change our thinking - to think more positively, and to believe in our students. So, for example, rather than immediately assuming that most, if not all, International students are likely to plagiarize essays, we can set the stage from the start by building a positive, supportive environment that seeks to educate rather than pontificate. Another quote from Katie's article below underscores my message:

“When we expect certain behaviors of others, we are likely to act in ways that make the expected behavior more likely to occur. (Rosenthal and Babad, 1985)”

Let's take plagiarism. I've often heard from colleagues both genuine concerns and negative comments/expectations of students in terms of plagiarism. This, in turn, leads to plagiarism being approached in an almost compelling manner within course materials: plagiarism is bad, and therefore if you plagiarize you are bad and so if you plagiarize, you will fail, etc.Using the above example, one relatively simple way to embed a positive approach to learning and teaching is to change the negative, hellfire-and-damnation discourse on plagiarism often present within course materials to one that offers an open, frank discussion on attribution and giving credit. One such way I have done this is by getting students to look up and understand attribution through discussion, and then following this up by reading an in-depth report on a politician who plagiarized a paper for a Master's degree. From what I have observed, these combined approaches give students a chance to explore the issue of plagiarism through a more empowering lens while exercising their academic literacies (digital and information among others).From what I have observed, these combined approaches give students a chance to explore the issue of plagiarism through a more empowering lens while exercising their academic literacies (digital and information among others). It gets them thinking and talking amongst each other rather than being spoken [down] to in terms of the issues of plagiarism. Along with the teacher creating an empathic, positive atmosphere, this also makes students feel part of the discussion and (more) part of the academic community as they seek to understand expectations that may be new and/or alien to previous educational experiences.Ultimately, the choice lies with the teacher in question to change their practices or not. There is always an element of risk to transforming teaching practices. However, without taking risks (even small ones) to innovate, one will simply never know how effective the changes to might be. Mulling ideas over is a good way to get started, but as with anything, mulling ideas over for an extremely long amount of time can kill ideas and innovation. Staff who have ideas should be allowed to experiment, and line managers should be proactive in supporting staff who are enthustic about learning and teaching.If things don't entirely work as planned or expected, well, at least learning has occurred on the part of both the learners and the teacher(s) in question. The light bulb and radio weren't perfected within a day's time, so why should a new teaching approach be perfected before trying it out?! Just do it!Just do it!