Getting students to use (new) apps

I've decided to quickly write up some thoughts on getting students to use new apps for learning and teaching as a reflection on what I've observed over the last few years and more recently.

It's safe to say that I approach this post from the point of view that there are many opportunities for digital education to enhance the learning and teaching experience.

More specifically, I'm writing this short article in relation to #MicrosoftTeams and what you need to do to ensure successful uptake by students and staff. What I write here applies to any other new systems - even ones such as Moodle.

Social media all around

It's fair to say that a lot of students and even staff in higher education use a variety of social media for various purposes. Students and staff still may use Facebook to connect with their friends and family, and classmates and course mates. Statista has a wealth of data on users of Facebook and Twitter, if you're interested.

Both of these groups may, if they're interested, use Instagram to create, collate and share images and/or video - photography and multimedia generally. A good number of students use Snapchat and in the UK high numbers of users aged 18-24 are likely to use Snapchat. Some university staff even use Snapchat to engage students in the classroom - with success!

Students aren't digital natives

A lot of my colleagues in higher education might understandably believe that because students regularly use apps like Snapchat, Instagram, WeChat, Facebook and others that this ability translates into a being able to effectively use digital tools and being tech savvy - being digital natives. - well beyond what my colleagues may have grown up with.

A lot of us use technology to 'passively soak up information' which could be scrolling through a Facebook or Instagram feed and reacting to posts. Yes, perhaps we share the odd image, video or article and add a bit of commentary - commentary - but are these acts critical or rather habitual?

I'd say these are habitual acts that form part of a series of daily routines in which users might fill time - gaps between spurts of attention to other things - and/or while navigating and exploring the vast ocean of information that's out there. From funny memes to noteworthy articles or click-bait news - it's all information, and it doesn't take much effort to open our favorite app to access that information! And this leads me to my main point...

New and unfamiliar systems

In a university setting, students will often use platforms such as Moodle, Blackboard, Google Apps for Education or similar. Microsoft has an answer, too, #MicrosoftTeams. All of these platforms offer a range of activities, structures and systems that can greatly help to manage the design, flow and presentation of information for users.

One thing we should not forget is that the aforementioned systems are created for the purposes of education, business and collaboration generally which go beyond the basic functions of Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram which are primarily for 1:1 or small group chats/discussions that are often centered around the sharing of media.

However, what unites all of these systems, platforms and apps for education is that generally these are unfamiliar to students unless there is a chance that they'd previously used one of them in school. Even then, if, for example, students have used Moodle in school, the look and feel of the system may not represent what they end up seeing in a university setting. Indeed, where modules on Moodle are still often used as repositories rather than engaging learning and teaching hubs, this can be daunting for users of 21st Century systems such as Google Search or Bing that offer information at your fingertips with few hurdles if you understand how to do key word searches. This leads me to a question:

How often do you explicitly train your students in using your university system or an app for a module?

I suspect not a lot of programmes take the time to explicitly provide training to students. That said, think of all the time we spend when we start a new post to receive training on the following:

- health & safety

- diversity

- data protection & GDPR

So why don't we spend a bit of time investing in the training of digital abilities and skills rather than assuming that the use of a smart phone = being digital and tech savvy? Taking a selfie does not make you a tech expert!

New systems require explicit training

#MicrosoftTeams is taking off as the latest app for learning, teaching and collaboration generally within higher education in the UK. Indeed, I'm using it on a module that I lead on and it's confirmed a few things that I learned a few years ago.

Between about 2014-2016, I was working with pre-sessional student who would come to the UK during the summertime period to study English as a foreign language for the purposes of improving their academic English language abilities. Students generally had an English language knowledge of about B1 to B2 and they had digital skills that ranged significantly. Nearly all had a smart phone and could use the main apps of the day.

We used Moodle as our online platform with our students to set readings, have online discussions and set assignments that students would write up, upload and submit. Moodle was a system most students hadn't used and would only use in their university studies. In order to ensure the students' success in using the online platform as an enabler rather than a distraction, I convinced colleagues to allow all students to receive 1 hour of explicit instruction on hows and whys of using Moodle.

During the summer, we had around 700 students over 3 cohorts that we needed to train up. So, we booked computer labs and trained students in groups of 30-50 each in the space of about 1 hour; there were frequently 3 staff (including myself) on hand to help out and ensure that everyone was on the same page.

Effective training = tangible benefits

Although with the sheer numbers of students to train some days were long, the result was that we were able to ensure that over 90-95% of the students understood what Moodle was and what it was for, why we were using it and how they could access it. This number was able to ensure that we had created a relatively strong community of learning in which students could support each other in understanding and practicing how to navigate an unfamiliar and new system, which in this case was Moodle.

As a side benefit, also important, for students whose first language wasn't English, they were able to understand that they were going to get a lot of writing practice in English, which would boost their confidence in writing more fluently (albeit not always accurately) in a relatively authentic, meaningful way that they could then transfer back into their own writing for essays and assignments.

Key takeaways

The key takeaway here is this: If we throw the apps at students, they don't always get it. They generally get Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat... because those are fun apps for fun, social stuff. They won't necessarily get apps for education, business and collaboration though; these aren't natural apps - they aren't always fun (or associated with fun!), so we should prepare our students first before letting the apps loose!

With nominal training (1 hour) students will:

- develop a critical awareness of the reasons for using the system;

- gain effective practice in using the basic, required elements of the new system;

- develop transferable digital skills that can be used for approaching and understanding new systems.

So, if you're going to teach on a module that involves Moodle, Microsoft Teams and/or similar, and/or if you have a student induction coming up, take the time to build in 1 hour of training.

The results will pay off and speak for themselves!

Thoughts on 'Why Believing in Your Students Matters' by Katie Martin

Today I came across this succinct article by Katie Martin on why believing in our students matters, as this can have a significant impact upon a teacher's practices and students' uptake of learning regardless of where learning and teaching that takes place - whether face-to-face or online.While I have known about the need to wait for responses from students for some time, and I value this approach, sometimes one can wait a bit too long. UK universities have had high and growing numbers of students from China for a while now. Some universities throw their doors open to International students since they pay higher fees.One such university near London where one Master's program of 150+ students has well over 95% of its students from China. At the same time, some of these same universities that seek to recruit large numbers of International students, often heavily reliant upon specific markets such as China, can, at times, lower the bar in terms of language requirements. From my own experience of observing and delivering teaching, this situation, which isn't unique to the aforementioned university, creates a number of issues since the students often:

Today I came across this succinct article by Katie Martin on why believing in our students matters, as this can have a significant impact upon a teacher's practices and students' uptake of learning regardless of where learning and teaching that takes place - whether face-to-face or online.While I have known about the need to wait for responses from students for some time, and I value this approach, sometimes one can wait a bit too long. UK universities have had high and growing numbers of students from China for a while now. Some universities throw their doors open to International students since they pay higher fees.One such university near London where one Master's program of 150+ students has well over 95% of its students from China. At the same time, some of these same universities that seek to recruit large numbers of International students, often heavily reliant upon specific markets such as China, can, at times, lower the bar in terms of language requirements. From my own experience of observing and delivering teaching, this situation, which isn't unique to the aforementioned university, creates a number of issues since the students often:

- come with different levels of language readiness for an intensive postgraduate level of study;

- are not or may not be used to interacting and socializing with those from other countries;

- are unlikely to work outside their 'peer' group of compatriots due to shyness, peer pressure or do so begrudgingly; and/or

- lack confidence in their own abilities and are perhaps not provided with enough motivation from teaching staff to instill a positive, 'can-do' attitude to learning.

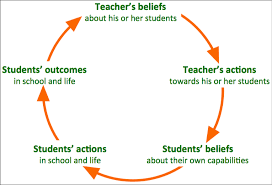

The result of any or a combination of these is that lecturers, academic tutors, learning developers and tutors of English for academic purposes are frequently put into tricky situations: the content has to be delivered, but if students are struggling to understand, what is to be done? Too often I have heard over the years, from staff at various institutions, similar negative remarks that Katie mentions in her article. I've always found these types of comments particularly demotivating and, silently, I ask myself upon hearing sustained negative comments "Well, why the hell are you in teaching?!" It is as if those making such comments were perfect students who always worked hard.On the flip side, the best colleagues I've had have always been positive, supportive and empathetic to the student journey. This empathy seems to set apart the negativity of the moaners from the teachers/lecturers whose lessons that we would always look forward to when we were once students. I think part of this empathy that some educators have is at least partially informed by the works of the Brazilian educationalist Paolo Freire, among others.Going back to Katie's article, I think one solution is creating a positive, welcoming environment that seeks to recognize the students as intelligent participants who are able to interact at Master's level successfully with regular, positive support that seeks to push the students' boundaries and to modify our teaching practices to engage the students in such a way that might tease out from them meaningful participation.One way, I believe, is to have a meaningful, welcoming induction to a program that gets students involved in getting to know their peers and teaching staff beyond the polite formalities of titles and names (think: basic teambuilding activities that get students to solve real problems related to their studies and/or life within their new educational setting). Oftentimes, I've seen inductions that were so superficially boring, stereotypical and/or dry that it immediately set the wrong (superficial) tone for the program of study in question.Another solution is to embed positive thinking throughout a program. As Katie says in her post:

... when we believe we can learn and improve through hard work and effort we can create the conditions and experiences that lead to increased achievement and improved outcomes.

In terms of learning and teaching, this is particularly powerful for our students. If they feel the above, they can and will improve in their learning journey. We, as educators, have a responsibility to instill these ideas into our students, especially International students who might genuinely need extra support, encouragement and motivation in order for them to become independent learners. Part of ensuring the success of our learners is to change our thinking - to think more positively, and to believe in our students.This also means we might need to change our approach to learning and teaching. So, for example, imagine you have a session of 15-50 students and they don't volunteer answers without being called on and prefer to stare at their phone or laptops (or both!). If our students are quiet and reticent to raise their hands to volunteer an answer, then there are some easily-doable solutions.

- Creating regularly-spaced questions to gauge/engage/formatively assess learning can significantly help improve participation, and these can be easily delivered via a response system such as Mentimeter or similar as students only need to use their mobile phone/phablet/tablet/laptop.

- Implementing a Twitter feed so that students can engage during/after a teaching session can also foster learning by using a module/course specific hashtag. These two blog posts have a range of good ideas:

Apart from those small solutions, I believe that part of ensuring the success of our learners is also to change our thinking - to think more positively, and to believe in our students. So, for example, rather than immediately assuming that most, if not all, International students are likely to plagiarize essays, we can set the stage from the start by building a positive, supportive environment that seeks to educate rather than pontificate. Another quote from Katie's article below underscores my message:

“When we expect certain behaviors of others, we are likely to act in ways that make the expected behavior more likely to occur. (Rosenthal and Babad, 1985)”

Let's take plagiarism. I've often heard from colleagues both genuine concerns and negative comments/expectations of students in terms of plagiarism. This, in turn, leads to plagiarism being approached in an almost compelling manner within course materials: plagiarism is bad, and therefore if you plagiarize you are bad and so if you plagiarize, you will fail, etc.Using the above example, one relatively simple way to embed a positive approach to learning and teaching is to change the negative, hellfire-and-damnation discourse on plagiarism often present within course materials to one that offers an open, frank discussion on attribution and giving credit. One such way I have done this is by getting students to look up and understand attribution through discussion, and then following this up by reading an in-depth report on a politician who plagiarized a paper for a Master's degree. From what I have observed, these combined approaches give students a chance to explore the issue of plagiarism through a more empowering lens while exercising their academic literacies (digital and information among others).From what I have observed, these combined approaches give students a chance to explore the issue of plagiarism through a more empowering lens while exercising their academic literacies (digital and information among others). It gets them thinking and talking amongst each other rather than being spoken [down] to in terms of the issues of plagiarism. Along with the teacher creating an empathic, positive atmosphere, this also makes students feel part of the discussion and (more) part of the academic community as they seek to understand expectations that may be new and/or alien to previous educational experiences.Ultimately, the choice lies with the teacher in question to change their practices or not. There is always an element of risk to transforming teaching practices. However, without taking risks (even small ones) to innovate, one will simply never know how effective the changes to might be. Mulling ideas over is a good way to get started, but as with anything, mulling ideas over for an extremely long amount of time can kill ideas and innovation. Staff who have ideas should be allowed to experiment, and line managers should be proactive in supporting staff who are enthustic about learning and teaching.If things don't entirely work as planned or expected, well, at least learning has occurred on the part of both the learners and the teacher(s) in question. The light bulb and radio weren't perfected within a day's time, so why should a new teaching approach be perfected before trying it out?! Just do it!Just do it!