Exploring ideas for decolonizing the curriculum using generative AI tools

In this post, I share some examples created by generative AI for decolonizing the curriculum. I also contextualize the examples by providing commentary from colleagues from the University of Glasgow Decolonising the Curriculum Community of Practice.

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

In this post, I share some examples created by generative AI for decolonizing the curriculum. I also contextualize the examples by providing commentary from colleagues from the University of Glasgow Decolonising the Curriculum Community of Practice.

Decolonizing education is part of many university strategies, including the university where I work. So, it seemed natural to think of how generative AI tools might help university students and staff think of ideas for decolonizing the curriculum. However, we must remember that the underlying logic of generative AI represents tools created by those in nations that hold power over others. Generative AI tools are often created in former imperial nations that seek out and obtain cheaper labor in other parts of the world to train and ‘develop’ the tools further. Generative AI also imparts a significant environmental impact, which must be considered.

AI and ethical considerations: coloniality of…

There are several caveats to using AI and generative AI generally, which I briefly outline in Karen Hao’s article from July 2020:

ghost work

this is invisible labor provided by underpaid workers who are often in former US and UK colonies (among others)

beta testing

sometimes beta testing is used on more vulnerable groups; yes, this is unethical, but it does still happen

AI governance

think about who creates governance for AI; high-wealth nations and the Global North largely drive this at the expense of Global South nations

international social development

if we consider ‘AI for…’ initiatives, we have to consider who drives these and who the targets or recipients are

algorithmic discrimination and oppression

if we consider who creates algorithms, then we can begin to understand why some algorithms can portray racist, gendered, xenophobic imagery

Further reading

To understand the ethical issues of generative AI by using a decolonial lens, have a read of these:

Hao, K. (2020). The problems AI has today go back centuries. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/07/31/1005824/decolonial-ai-for-everyone/

Hosseini, D. (2023). Generative AI: a problematic illustration of the intersections of racialized gender, race, ethnicity. https://www.dustinhosseini.com/blog/2023/08/08/generative-ai-a-problematic-illustration-of-the-intersections-of-racialized-gender-race-ethnicity

Mohamed, S., Png, M. T., & Isaac, W. (2020). Decolonial AI: Decolonial theory as sociotechnical foresight in artificial intelligence. Philosophy & Technology, 33, 659-684. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13347-020-00405-8

Zembylas, M. (2023). A decolonial approach to AI in higher education teaching and learning: Strategies for undoing the ethics of digital neocolonialism. Learning, Media and Technology, 48(1), 25-37. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17439884.2021.2010094?casa_token=qQjMpifVSaAAAAAA%3AZlWVF-kVnHnzHnF7B9zTow4mZUftx7rwKvnWYNkjAeHYu8BX2hxYXAMtE-F0HNO5WCctYblypLVU

Generative AI’s suggestions for decolonizing

For the following outputs, as shown in the GIF images below, I used the initial prompt:

I'm a lecturer and there is talk of decolonising the curriculum. I teach mathematics and statistics. What can I do to start decolonising my curriculum?

As we can see in the GIFs below, each generative AI tool appears to give some considered suggestions for how a lecturer in this particular area might go about decolonizing the curriculum they teach. Ideas such as incorporating more diverse views, Indigenous knowledges and contextualizing what is being learned are all general suggestions that I might expect to find in such a curriculum that is undertaking decolonizing.

However, I wanted to see more detail and so I followed up with another prompt.

The follow-up prompt was designed to see what else generative AI might suggest. Interestingly, with insight from colleagues, plenty could be done and suggested to create a curriculum that undertakes decolonization within a specific context.

In this case, the lists seemed familiar and similar in some respects and then a bit different in other respects in ways that I couldn’t immediately pick up on. The suggested names stem from ancient to modern times, albeit with a jump between ancient and modern times! Some familiar names are there, but are there perhaps some that could be included?

Here is the prompt I used:

What are some prominent but overlooked non-Western scholars of mathematics and statistics?

Reflections from colleagues

I consulted some colleagues, given the topic, the example is from an area I’m not familiar with. Specifically, I consulted colleagues in the UofG Decolonising the Curriculum Community of Practice who kindly provided their thoughts.

Soryia Siddique, whose background is in chemistry/pharmaceuticals/politics, provided the following:

My initial observation is that we ensure women of colour are represented in the materials. Perhaps a specific search around this.

BAME and Muslim women are underrepresented in many professions, including senior roles in Scotland, and are likely to experience systemic bias. Taking into consideration that Muslim women can experience racisim, sexism, and Islamaphobia. It is questionable whether media/society represents Muslim and BAME women's current and historical achievements.

They are also "missing” from Scotland’s media landscape.

In utilising AI, are we relying on data that is embedded in algorithmic bias and potentially perpetuating further inequality?

Soryia also suggested the following reading: The Movement to Decolonize AI: Centering Dignity Over Dependency from Standford University’s Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. It’s an interview with Sabelo Mhlambi who describes the role of AI in colonization and how activists can counter this.

Samuel Skipsey, whose background is in physics and astronomy, also shared his thoughts:

The "list of important non-Westerners" is fairly comparable between the two - Bard is more biased towards historical examples and is pretty India-centric (with no Chinese or Japanese examples, notably), ChatGPT does a lot better at covering a wider baseline of "top hits" across the world (although given that "Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art" doesn't have known authors - the tradition of the time it was written means that it probably had many contributions whose authorship is lost to history - I would quibble about it being a "scholar"). I note that this is still a Northern-Hemisphere centric list from both - although that's somewhat expected due to the problems citing material from pre-colonial Latin America, say. Still, it would have been nice to see some citation of contributions from Egypt, say.

In general, both lists are subsets of the list I would have produced by doing some Wikipedia diving.

The "advice on decolonising" is very high-level and tick-boxy from both. It feels like they're sourced from a web search (and, indeed, on an experimental search on DDG [DuckDuckGo] for "how can I decolonise my course" the first few hits all have a set of bullet points similar to those produced by the LLMs, which is unsurprising). To be fair to the LLMs, this is also basically what a lot of "how do I start decolonising" materials look like when produced by humans, so...

As Soryia notes, because the answers are quite generic there's a bunch of specific considerations that they don't touch on (they're not very intersectional - Hypatia turns up on both lists of non-Western scholars, doing a lot of heavy lifting as the only female name on either!)

Experimenting with generative AI: (re)designing courses and rubrics

In this post, I share some ideas for (re)creating courses and assessment rubrics as well as getting ideas for creative assessments using generative AI.

Experimenting for creating a course

I tried out Google Bard and chatGPT 3.5 to design courses and rubrics. In each case, being specific about what I wanted to see created was key. What this means is that when you are creating your prompt or query, you should be specific in terms of:

Context: e.g. state who you are or who you imagine yourself to be when creating the prompt

Audience: who is the audience of what you want to create? Students? Staff? Administrators? Management? The Public?

Purpose: in brief terms, what do you want to achieve?

Scope: similar to context, however, I see this as more focused, so ‘create a university level course on sociology’ is fine, but narrowing it down to ‘Year 1, Year 2’ etc. will focus the prompt and subsequently generate examples more tightly.

Length: it’s always helpful to state the length of the proposed course or output. For example, are you asking for a draft of a 12-week course? A two-page maximum syllabus? A three-paragraph summary?

For this example, I used the following prompt…

I am a lecturer who teaches university-level chemistry. I wish to create a new course on inorganic chemistry for Year 2 university students. The course should be 12 weeks long and have 4 assignments. What might this look like?

Below are two GIFs showing chatGPT and Google Bard respectively.

NB: You may wish to select the images to see a larger version.

Brief reflections

I used a similar prompt for both generative AI tools. I decided to add an element of creativity when so I slightly changed the prompt when using Google Bard to get it to suggest creative assessments. I then went back to chatGPT to ask it do also suggest ideas for creative assessments within the context of this course.

They seem to produce similar results regarding this particular prompt. Both suggest an outline of a suggested course on inorganic chemistry; while Google Bard integrates the creative assessments into some of the topics, chatGPT predictably creates a list of suggested creative assessments as I had asked it after the initial prompt.

Interestingly, Google Bard also expands a bit at the end of the outline with further examples of non-written, creative assessments. chatGPT, on the other hand, does give some examples of ways of supporting learning and teaching after creating an example course outline. The creative assessments it lists are similar to those of Google Bard, although they are different, such as the quiz show example among others.

For transparency, I do not teach chemistry nor have I taught it. I have, however, supported those learning chemistry with their academic writing abilities, including writing lab reports and researching the topic. On the surface, the course looks coherent. However, I will leave that to those who teach chemistry!

What you can do

To replicate what I’ve done, copy and paste the prompt into your generative AI tool of choice.

Please note: you’ll likely get a slightly different response. I did not test each response again. That said, Google Bard automatically offers additional draft examples.

Creating assessment rubrics

Educators are often handed marking rubrics with little chance to develop or create their own. What this means is that when it comes to creating an assessment rubric, some educators may not have practical experience beyond what they have observed. In this case, generative AI can provide ideas and food for thought. This can be especially helpful for getting ideas for creative assessments that are still valid and rigorous while offering a suitable alternative to traditional assessments.

I ask generative AI tools to create assessment rubrics in the examples below. Remember: you need to give generative AI a context (e.g. you’re a lecturer teaching X), a specific request (e.g. you want to create an assessment rubric) and ensure the request has specific parameters (e.g. you provide your specific criteria for this rubric) .

I am a lecturer. I wish to create a marking rubric for an essay-based assessment. The rubric should include the following criteria: criticality, academic rigor, references to research, style and formatting.

NB: You may wish to select the images to see a larger version.

Reflections

In both cases, I state my (imagined) role and the type of assessment I usually employ and ask the tools to suggest ideas with specific criteria included. In both cases, each generative AI tool creates a sample rubric based upon what I have asked it.

Both tools create a table I would expect an assessment rubric to look like. Each table includes the criteria and sample grade bands with descriptor text that cross-references to the criteria. What both generally do well with is providing some sample descriptor text. However, you will need to tweak, modify and/or change the criteria to your specific, local context.

Creating rubrics specific to your institution

If your institution has a general, overarching rubric often used, you can get generative AI to suggest sample rubrics. This may, however, be difficult given how complex your institution’s rubric may be.

In the examples below, I ask chatGPT 3.5 and Google Bard respectively to create an example rubric based on Glasgow University’s 22-point marking system. This did, however, prove difficult!

Can you change the marking scale to a 22 point scale used at the University of Glasgow?

Reflections

The prompt above initially confused both generative AI tools. This could be because a 22-point scale differs from many scales out there. This could also be because I hadn’t provided specific context of the different bands. In this case, my suggestion is to suggest that chatGPT or Google Bard create a rubric based on your marking criteria. You can then tailor the created sample rubric to your local needs.

As you can see, both tools got some areas right and others wrong.

What chatGPT did well:

it created a scale based on the criteria I provided

it included the marking bands, cross-referenced against the criteria

it included some basic descriptor text

What chatGPT can do better at:

the descriptor texts were wildly off compared with the example marking schemes

it struggled to capture the nuances between the marking bands

What Google Bard did well:

the descriptor text for each band more closely matches what I would expect to see

the marking bands are divided out nicely

the criteria are cross-referenced against marking bands

What Google Bard can do better at:

it’s hard to say what it can do better at right now given how it created a marking rubric based upon my query!

that said, the descriptor texts for each band would likely need some tweaking to match local styles

Getting ideas for creative assessments

As I noted earlier, you can use generative AI to get ideas for (more) creative assessments that aren’t traditional, written-based assignments. Traditional, written-only assignments are great for some things. However, there are other, more inclusive and creative ideas for assessments that you can use in your teaching, no matter the subject.

For this particular example, I draw upon my own area of expertise and subject area which lies at the intersections of education and sociology.

I teach a social sciences subject in university. Traditionally, we use written assessments such as essays and exams as assessments. What are some creative alternative assessments?

Reflections

In brief, similar to the first example on chemistry, both generative AI tools create a good range of creative and event collaborative assessments that you can use within your own context.

You may already use some of these, such as mind maps and portfolios. That said, there are a lot of good ideas that have been suggested that might be worth trying out. I would recommend co-creating these with students, especially if an idea appears new or innovative or out of your personal comfort zone as an educator. You may be surprised at how quickly your students take to becoming partners in learning and teaching.

Reflections on work - from the past

I originally authored this post in April 2020 not too long after the COVID-19 pandemic caused cities and nations to lockdown. I found this as a draft post that I hadn’t published perhaps due to all that was going on at the time.

What I wrote here in April 2020, still holds in September 2023.

An image of a person standing on still water, which causes a reflection of the mountains and sky. Source: Unsplash

“If we cannot recognize the truth, then it cannot liberate us from untruth. To know the truth is to prepare for it; for it is not mainly reflection and theory. Truth is divine action entering our lives and creating the human action of liberation.”

Reflections on work

I've worked as a 'digital education facilitator / senior teaching associate' for almost 3.5 years at the Lancaster University Management School. I arrived hopeful, looking ahead to entering a new phase of my career within higher education where I would be explicitly working with a range of colleagues - academics, administrators, subject librarians and students - to develop both blended and online learning experiences. My time in my current role is coming to an end as I plan to move on to a new challenge and to both undertake a doctorate. In many ways, it makes sense to do these in the same place. In this post, I share some thoughts, reflections and hopes.

Synergy is key, when enacted

My current role is based in a large management school - a business school - where you have a range of business subjects divided into departments ranging from Accounting and Finance; Economics; Organization, Work and Technology; Management Science; and Marketing. There is also the Undergraduate Office where consortial programmes are situated.

One of the best part of working in such a large school was getting to meet a range of people from all walks of life and experiences. There are a lot of colleagues who care about their students. Indeed, the Dean at the time of this writing has had a project that sought to develop a cross-departmental community for students which takes the form of a module called MNGT160: Future Global Leaders: Sustainability Across Business.

This module has often been a source of contention as it sought to create a community that cuts across departmental boundaries, and thus, requires both contribution from each department and some hours to be workloaded from each department. Since it is not 'owned' by any one department, this module has, at times, not received a welcoming view. However, the aim and ethos of the module are fairly sound: to create a community while developing some graduate attributes within students through getting them to work together across their subject silos. Idealistic? Perhaps. Doable? Definitely.

With the amount of expertise and experience across the management school, such a module has great potential to create a very collaborative, cross-departmental community of learning and teaching that could strengthen the identity of the school itself while creating networks of students (and staff) who could work closely together in order to grow, develop as students, people and future professionals and subject experts.

Synergy is key for such a module to happen. Working together and drawing upon the expertise of such a large school to create good curricula, well-structured systems and a positive, welcoming environment for learning can only be a good thing surely.

The pandemic and the move to digital

Covid19 has upended a lot of systems, processes and practices. Initially, there was a lot of uncertainty that allowed some leaders to emerge in order to mitigate some for the panic and anxiety that the sudden shift or pivot to digital education that the pandemic caused.

During these first weeks and months, a lot of educational technologists were doing their utmost to help staff however and wherever possible. In fact, this is still continuing. What has been at the back of our minds - some of us - has been those little fleeting thoughts of ah, if we only had more blended learning before, we'd be more prepared for this!

Of course, learning/educational technologists have been trying for years to get academic and teaching staff to integrate in the digital into learning and teaching. We do this because we understand that, on the whole, students require a full range of digital literacies in order to live and work within the 21st Century to the full. People can live without collaborative and smart technologies, sure, but the world is generally progressing in the direction of closer collaboration and working together through digital means. Sustainability, efficiency and richness of opportunities are just a few reasons that digital literacies and their development are so key for the future. We could not have predicted the pandemic, nor used this as part of a rationale for integrating digital education practices for sounding, at best, alarmist.

That all said, what the pandemic has caused for digital education is a few points:

a sudden, renewed interest in digital education, whether blended or fully online;

a deeper understanding of working and studying at home, and how this can work;

a better appreciation for educational technologists and those who have integrated digital education practices into their teaching;

the development of a range of solutions to address issues arising around learning and teaching both remotely and at a distance;

and many others.

The fourth point is particularly interesting for me within my current role because I have been able to observe developments locally, nationally and internationally through a mixture of professional networks sustained by email lists, social networks on Microsoft Teams and Facebook and looser networks on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Working in silos: missed opportunities

Initially, I observed the same questions arising from the different places. I frequently saw the same or very similar questions coming from a range of staff that mostly where 'how to?' questions. I helped wherever I could by providing advice, solution and consultations where appropriate.

I began observing with a bit of annoyance and sense of powerlessness a pattern that slowly began to develop: colleagues were working in their departmental silos to create solutions. These solutions were not always shared across the departments at a macro level. As far as I was concerned, given my role and position that allowed somewhat of an overseeing eye, if I did not hear about it, I believed that a potentially valuable idea was not being shared to colleagues whom might need or find value in such solutions.

To my mind, this type of working did not make sense for a few reasons:

the problems themselves are common across the faculties - the 'how to?' questions;

solutions/ideas created in silos and thus not shared is, in effect, a replication of effort;

those with the most experience within digital education were not always consulted first despite their expertise, and in effect, time and attention was misused;

Generative AI: a problematic illustration of the intersections of racialized gender, race, ethnicity

NB: this post is a draft and subject to change; it forms a pre-print (an author’s original manuscript) I have authored.

Learning, teaching and technology have often been a big part of my career - since way back to the mid/late-2000s! Now in 2023, talk of artificial intelligence and education is omnipresent, and it's here to stay. Machine learning allows AI tools to become more intelligent by drawing on datasets to develop expertise over time. However, AI tools rely upon raw data created by humans; these datasets, in turn, reflect the biases of those who have gathered the evidence, which will be racial, economic and gendered in nature (Benjamin, 2019, p. 59).

Several researchers (Noble, 2018; Benjamin, 2019; Mohamed et al., 2020; Zembylas, 2023) are looking into the underpinning reasons that enable AI to skew results and create representations that overlook and erase others while focusing on specific, dominant groups. Specifically, the way that the human-created algorithms informing AI and generative AI tools portray racialized, gendered people is especially problematic. To understand why problematic representations of people are created, it is worth looking at the ideas of intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991; hooks, b, 2015; Hill Collins, 2019). I draw on bell hooks and Patricia Hill Collins’s works here and recommend the reader acquaint themselves with Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work.

I write this post from my position as a part-time doctoral student, educator and higher education worker at a Scottish university in the UK. I write it as someone who’s interested in and curious about technology and as someone who teaches, develops, coaches. mentors educators (lecturers) how to teach and augment their teaching practices. However, I also write it from the perspective of a US migrant and dual national who has lived/worked in China, Russia, Kazakhstan and the UK. I note these as they inform my positionality when writing this post as I am interested in the interplay of education, culture, media representation, critical pedagogy and decolonial thinking as some of the ideas underpinning these areas inform some of my personal and professional values.

As a colleague of mine wrote "As per the Russell Group principles, I strongly believe it’s my job as an individual educator and our job as a sector to guide students how to use AI appropriately." I take their words and apply them to my own context: I believe it is my job as an educator to guide students and university staff in understanding and using AI appropriately.

For educators, this will give you an insight into some of the affordances of generative AI tools for creating images while exposing you to some of the opportunities and serious problems of using, for example, DALL-E, to create images. This post should give you ideas for developing your own practice with your students and your colleagues, no matter their experience as educators.

Thank you to colleagues and friends who have helped expand my thinking when writing this post.

Introduction

Using generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools can be exciting, confounding, scary and confusing. This was my experience and observation upon showing an academic colleague how a generative AI tool like ChatGPT can work by taking text prompts that are then create text-based content. Although text content creation tools have been at the forefront of everyone's mind since at least mid-2022, there are other generative AI tools that exist and merit attention. At the time of this writing, I can see common generative AI tools being categorized into three or four major types:

text to text (e.g. ChatGPT, Google Bard, Cohere.ai)

text to image (e.g. DALL-E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion)

text to media, such as audio or video

and text-to-code, for coding and programming purposes

In this post, I focus on text-to-image generative AI through example prompts that I created. I analyze what it produced to demonstrate that educators must experiment with generative AI tools to understand and critique the tools and what they produce. In doing so, we can begin to understand how and why such tools create the content that they do. I use intersectionality as a heuristic (Hill Collins, 2019) to analyze the AI-generated avatars by looking at how these represent socially constructed identities in terms of racialized gender, race, ethnicity and nationality. Humans create algorithms and algorithms, in turn, create representations based upon human-created algorithms.

Specifically, we can deepen our understanding the reasons that generative AI tools (and other technologies) create questionable content that might, at the very least, underpinned by stereotypes representing an intersection of racism, misogyny, classism and/or xenophobia.

Finally, we must recognize that, for the moment, there is no concrete solution that a lay academic or layperson can implement to achieve this without a collective, concerted effort that includes a range of groups focused on shining light on the issues, changing hearts, minds and code and imaging ways forward to an equitable, inclusive world. Decolonial thinking can offer some imaginations to counter the coloniality of AI.

I first provide the context by laying out four (4) example prompts that I created an entered into DALL-E. I briefly touch on the prompts I created before moving on to analyze the results of each of the prompts. I provide a basic critique of the subsequently created representations by looking at the atmosphere, decor, clothing, facial expressions, ethnicity, or race.

For clarity, I use definitions of race and ethnicity offered by Fitzgerald (2020, p. 12) that sees race as referring to a ‘group of people that share some socially defined characteristics, for instance, skin color, hair texture, or facial features’ while ethnicity encompasses the ‘culture, nationality, ancestry and/or language’ shared by a group of people irrespective of their physical appearance (ibid). Grosfoguel offers another take on race informed by decolonial thinking: race is what he terms ‘a dividing line that cuts across multiple power relations such as class, sexual and gender at a global scale (2016, p. 11). In this case, race and subsequent racism are institutional and structural in nature in that the concept of race creates hierarchies of power and domination which are compounded by gender, sex, class and other factors.

While the concepts of race and ethnicity are social constructs and neither are mutually exclusive, I use these definitions to frame my analysis.

I highlight what is represented, and why the representations might appear this way and leave you, the reader, with critical questions to consider as you and your prospective students/learners explore the usage of generative AI for creating images from text. I then offer some possible solutions drawing on decolonial thinking.

NB: some readers will find the results disturbing, upsetting and potentially angering.

Sweet old grannies

Generative AI allows us to experiment with ideas to then create representations of those ideas, whether these are text, images or other media. In these short cases, I asked DALL-E to create illustrations of sweet old grannies making pancakes. As a reminder, DALL-E is one of three major text-to-image generative AI tools, and there are many others out there.

This was an impromptu idea that came up for a few reasons. In my current role, there is much discussion on the issues of generative AI and how to prepare students and educators. I also like pancakes and I have some fond memories of one of my grandmothers who would visit regularly when I was younger. I also worked and lived in Russia for a while where both pancakes and grandmothers are a big part of the culture. Pancakes are big around Maslenitsa or Carnival as it is known in other countries that celebrate the Western Christian version of the event, while grandmothers are a major cultural symbol, source of unpaid family work (Utrata, 2008) and symbol of stoicism that represents an intersection of age, gender and class (Shadrina, 2022). I also thought it would be playful and also allow me to see how DALL-E, a tool created by humans who programmed algorithms, would represent humans.

For transparency, I acknowledge that I am using gendered, ageist and even stereotypical language, especially in terms of describing 'a sweet, old X grandmother'. I am also aware that I am focused on a particular type of social/familial role, a grandmother. Not all old(er) women are grandmothers and not all grandmothers are old! As Benjamin (2019, pp. 102 drawing on Blay, 2011) asserts, qualifying words - those adjectival words used to describe 'opinion, size, age, shape, colour, origin, material, purpose' (Dowling, 2016) often encode gender; race, racism and racialization; and the humanity of individuals and groups of individuals (see Wynter, 2003).

Initial prompts

I used a prompt and only changed the adjectival qualifier describing the national origin of the imaginary character or avatar: "Create an image of a sweet, old X grandmother making pancakes". I tried out these prompts over a period of two weeks in July 2023. The queries I created are these:

"Create an image of a sweet, old Polish grandmother making pancakes"

"Create an image of a sweet, old Russian grandmother making pancakes"

"Create an image of a sweet, old American grandmother making pancakes"

"Create an image of a sweet, old Black American grandmother making pancakes"

I use specific terms to get the generative AI tool DALL-E to generate specific results to allow me to see what the AI tool produces so that I can then analyze the results. This, in turn, offers evidence and clues to understanding how human-created algorithms create the outputs that they do within generative AI tools.

In each case, DALL-E created four (4) individual representations of each character or avatar to illustrate the prompt I had created; in total, there are 16 images which you can see below with a caveat. Generative AI does not currently do well with the finer details of humans such as facial expressions, eyes, and hands. While I won't focus on hands and eyes specifically, facial expressions and ethnicity will be important later.

Representations of Polish and Russian grandmothers

At first glance, to the untrained eye and perhaps even to the untravelled eye, we might think nothing is amiss. There are four different images created that seemingly portray what is meant to be a sweet old Polish grandmother who is making pancakes, and another four representing Russian counterparts. Generative AI does not currently do well with the finer details of humans such as facial expressions, eyes, and hands. While I won't focus on hands and eyes specifically, facial expressions will be important later.

Atmosphere, decor, clothing

As we can see, each image illustrates a sweet, old Polish grandmother who appears to be in an almost gloomy environment. The lighting isn't bright but rather dark and almost shadowy. The representations of their Russian counterparts are very similar in many ways: the atmosphere is dark, perhaps gloomy. We can see what looks like wooden utensils being used and in some of the windows, we can see stereotypical lattice-type window net curtains.

Such portrayals could indicate a lack of modern lighting and/or electricity. The light also indicates the time of day, which could be an early morning golden hour, when they might rise to make an early morning breakfast. This does offer a stereotyped, ageist view of the women represented, however, by generalizing that all might rise at a very early hour to make pancakes.

If we look at the clothing, we see that each avatar is wearing clothing that is stereotypical of elderly Polish and Russian women: patterns that are floral in nature while headscarves. Some women do occasionally wear headscarves when attending church. However, these women are depicted in the home. However, we don't really get any indication of their hair or hairstyles, or whether these are things they might worry about simply because the representations cover or hide this particular aspect of all of these women.

In each case, it seems that perhaps these avatar-grandmothers are living in a different time based on the depictions of the atmosphere and technologies they are using. This doesn't mean that some do not live this way, however, it is problematic as certainly not all might live this way depending upon their means, wealth and family ties.

Expressions and ethnicity

The expressions of the Polish and Russian grandmothers are problematic for a few reasons. If we look at each of the women, most of them appear to be looking either down or away with only one of each looking ahead at the imaginary camera. The images as a collective might be seen to represent a sort of melancholic and depressing environment.

The women are either expressionless or perhaps seemingly unhappy in the eyes of someone from the US or UK apart from one of the Polish avatars. While there may be socio-historic rationales for portraying the women in such a way (e.g., World War I and World War II, followed by the Cold War) these images are explicitly problematic as they represent stereotyped, gendered and xenophobic representations of elderly Polish and Russian women.

In terms of ethnicity, for both the images representing these groups, all of the women are White or appear to be White. Poland, according to some statistics is 98% Polish so perhaps the representations are close to portraying the norm. On the other hand, Russia is more complex with its 193 ethnic groups yet the images portray a high level of homogeneity.

Ethnic Russians make up 77-81% of Russia's population of 147 million, along with Tatars, Ukrainians, Baskhirs, Chuvashs, Chechens and Armenians being other major ethnic groups of over a million (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Russia#Ethnic_groups and https://minorityrights.org/country/russian-federation/ for a breakdown; there are other Russian-language sites that you can check as well). My point is here that Russia is a diverse nation of peoples of ethnic backgrounds and mixes including those of Slavic, Turkic, Caucasian, Mongolian peoples, indigenous and Korean ancestry. However, the images created by DALL-E portray avatars that represent only those who appear Slavic and/or European (i.e. White). There are no representations of other types of Russians who may be Turkic, indigenous, or Mongolian in origin.

However, this could be due to how algorithms encode the concept of a Russian person. Does 'Russian' mean a citizen of Russia, and therefore anyone who lives in Russia? If this is the case, then it is likely dominant views that inform datasets will skew any possible representations. On the other hand, does it mean those that see themselves as ethnically Russian? If this is the case, then perhaps it is valid to show only Slavic/European avatars. In either case, the representations are problematic as they highlight whatever the dominant 'norm' is while erasing Russia's historically rich diversity. Another perspective could be how a particular government might influence how the imaginations of its populace are portrayed, which may mean the prominence of a dominant group at the expense of an ethnic minority group. In Russia’s case, there are concerns surrounding ethnic separatism and how migrants are portrayed, especially of those from regions traditionally associated with Turkic and Asiatic peoples and those whose faith is Islam (Coalson, 2023). However, such concerns are not reasons for erasing different representations and portrayals of peoples of different ethnicities.

Representations of grandmothers from the US

As a reminder, I used the following prompt: "Create an image of a sweet, old American grandmother making pancakes". I acknowledge that using ‘American’ can be problematic. It can refer to people of the United States, or if you live in Latin America, American can refer to anyone from the Americas, not just people who live in the United States of America.

In addition to the term ‘American’ being problematic, this prompt quickly revealed more serious issues that I will touch upon.

Atmosphere, decor, clothing

The images of American grandmothers offer a stark contrast in many ways when compared with the representation of Polish and Russian grandmothers. The DALL-E produced illustrations appear to show these women, for the most part, in a different light.

While the first two women in the top row appear to be in the home, their homes appear to be more modern in some respects. They all appear to be using what appear to be metallic utensils as opposed to wooden ones. The lighting in the bottom two images is much brighter with almost an appearance of a representation of a cooking show as indicated by the lighter-colored walls. The atmosphere appears a lot less cluttered and lighter in many respects. This lack of clutter and more light might indicate, at the very least, modern homes that are efficient.

Then there are the hairstyles. These are, admittedly, something that I hadn't picked up on as it wasn't something that I am fully literate about until a friend prompted me. As that friend noted, the hair of these women tells another side of the story related to class. What does the hair say to you? How do each of their hairstyles represent their own lives? What does each style say about their socio-economic background?

The clothing also offers clues to how these avatar-representations live. Their clothes appear more modern, perhaps more expensive than their Polish and Russian counterparts. What does this say about the data that has informed the creation of these avatars?

Expressions and race

If we look at the facial expressions, again while generative AI does not yet get the finer details right, something appears and feels more warm, perhaps more positive about the expressions of these avatar women. The first one appears thoughtful and focused on what she is doing with almost a sense of enjoyment. The second one appears content - at the very least - with what she is doing. The third and fourth images appear to represent a wholly positive image of two different women engaging in cooking as indicated by slight smiles whether looking down (image 3) or looking straight ahead (image 4).

However, there is a significant problem with these representations which is indicated by the perceived race of the sweet, old, American grandmothers: each avatar represents a White woman. This is particularly problematic as the US has a population of over 330 million with nearly 80 million (nearly 1 in 4 people) who comprise non-White people. The question here then is why has the generative AI tool created only White faces to represent the qualifier ‘American’ when 1 in 4 people in the US fall under the broad categories of Black, Asian, Indigenous and others? Why is the US portrayed as, at least according to these AI-generated images, representing only one part of its population?

Representations of grandmothers from the US racialized as Black

Atmosphere, decor, clothing

If we consider the representations generated by DALL-E below, we see deeply problematic underlying issues that represent an intersection of race, gender and class in the portrayals of imagined sweet, old Black American women.

The atmosphere in each avatar appears generally warm and inviting, reflecting the representations of sweet, old, ‘American’ grandmothers. There is a certain simplicity and modernness to the environment. Two avatars appear in a home kitchen (the bottom two) as indicated by kitchen cabinets/cupboards and a nearby window. The top-left image appears perhaps in a larger, commercial kitchen or perhaps a kitchen in the home, and the second (top-right) appears perhaps in a TV studio as indicated by the lighting and focus.

One colleague, Dr Ruby Zelzer, notes something that I had missed:

… something struck me about how utilitarian the kitchens were, the kitchen tiles in 3 of the 4 pictures, and also that the type of tiles were very basic in appearance. How none of the other images had these tiles (to my eye).

However, the images appear to say something about the roles of these avatar women. Three of the images appear to represent the avatars as cooks or chefs, as indicated by what appear to be chefs' hats and their attire in general. The avatar in a pink apron and white outfit (top-right) appears to be in an ambiguous situation in part due to the lighting and the red nose: are they in a TV studio or in a circus? I will discuss this later as the representation harks back to minstrelsy and blackface.

In addition, two of the avatar women are wearing what look like cleaner gloves. The avatar portraying yellow gloves is also problematic as the gloves appear slightly worn and tattered. This can be seen to place someone, or here an older Black American woman, in a lower socio-economic position.

In 3 out of the 4 images (all bar the lower-left image), the avatars representing Black American grandmothers are situated in positions of service through the attire that they are portrayed to be wearing. In fact, only the avatar in a blue shirt and pink apron appears to be in a position that seemingly isn’t attributable to a service role. In contrast, the White representations of American women don’t appear to be in positions of service as indicated by their clothing. I now turn to discuss the problems that nearly all of these images is (re)producing.

Expressions and race

All the women appear to be smiling or enjoying what they are doing. At first, this may seem like a good thing. However, the expressions of the top-left and bottom-right avatars are highly problematic for a few historic reasons rooted in racist, gendered and classist portrayals of Black American women. In addition, the larger bodies of three of the other avatars also reflect how Black American women have historically been portrayed within the United States and beyond. In contrast, the avatars representing White American women are constructed with what appear to be more delicate and smaller features, something that several researchers (Bowdre, 2006; Downing, 2007; Thompson Moore, 2021) argue has frequently been attributed to representations of White women.

The origins of stereotyped representations of Black American women lie, in part, in minstrelsy in the 1800s (Bowdre, 2006; Downing, 2007; Thompson Moore, 2021). In minstrel shows, White men portrayed Black Americans by blackening their faces using burnt cork while exaggerating other facial features, such as the lips, by using 'red or white paint' (Bowdre, 2006, p. 37). The avatars representing Black American women are illustrative of how Black women were constructed in minstrel shows through the caricature of the wench (Thompson Moore, 2021, p. 318). White men performed the wench character representing Black women through cross-dressing and drag performances (ibid). Other characters would go further by dressing in 'brighter, more flamboyant dress' and their faces would be further exaggerated by makeup, creating 'larger eyes and gaping mouths with huge lips' (ibid). As Bowdre (2006) asserts, minstrelsy has aided stereotypes around people racialized as Black and continues to inform media representations of Black American men and women in the present day.

Another representation is that of Black American women as a ‘mammy,’ or a good-natured, submissive and motherly figure who would provide care for White families. Taken together, an excerpt from King (2019, p. 13) explains why such representations are deeply problematic:

“Aunt Jemima,” a well-known trope that (mis)represents/distorts Black/African womanhood in the USA, is a fictional historic advertising icon that reinforces the national stereotype of the slave plantation “mammy.” In the late 19th century, this image of a smiling, usually corpulent dark-skinned Black woman wearing a red bandana became the trademark logo for a technological innovation: ready-mixed pancake flour. Commercial advertisements that invented this denigrating image of Black womanhood expressed the white imagination, which was then reified in film, fiction, the fantasy world of plantation mythology, and consumer consciousness. This stereotype epitomises the dominance of hegemonic white memory and imagination in the material culture of American society (Wallace-Sanders 2008).

The images below depict what hooks (2015, pp. 65-66) would argue that such images portray Black women in a negative light through the construction of Black women having ‘excessive make-up,’ ‘wearing wigs and clothes that give the appearance of being overweight’ while simultaneously representing large ‘maternal figures’. bell hooks's message here is that historical depictions of Black American women portray them as fat/obese, older, asexual and unkempt, homogenizing this group while mocking them through the ‘wench’ and/or ‘mammy’ stereotypes, which both (re)produce demeaning representations of Black American women.

Discussion

What we see here in each of the images represents what are what Benjamin describes as (2019, p. 59) ‘deeply ingrained cultural prejudices’ and ‘biases’ drawn from data that the generative AI tools use to create representations.

While the imaginary representation of Black American women was reified in media and consumer consciousness, we can see that this portrayal resurfaces in the digital realm within the context of generative AI. What we see here then is one manifestation of ‘algorithmic coloniality’ (Mohamed et al., 2020; Zembylas, 2023). For those new to the concept of coloniality, this is a state of knowing and being that pervades knowledge and power relations that sees those formerly colonized and/or enslaved as regularly encountering inherent disadvantages in all aspects of life while former colonizers retain many advantages in all areas of life (Quijano and Ennis, 2000; Wynter, 2003; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2015). In simple terms, this means that accepted knowledges and ways of being represent those of the dominant members of society.

In this case, the role of Silicon Valley, located in the United States, which is a hegemonic power and an extension of the former European colonial nations as one of her settler-colonies, is significant. This extends beyond the technological companies of Silicon Valley and elsewhere in the US to anywhere that readily accepts, uses and replicates their models. Those who follow the dominant modes of cultural, and technological production take part in the creation and perpetuation of algorithms which overvalue some humans (those racialized as White) while undervaluing and actively devaluing the humanity of other humans (those racialized as Black, Asian and others).

Considering the #BlackLivesMatter movement and the daily injustices that people racialized as Black in the US (and elsewhere, even the UK for example) experience, it is particularly problematic that human-authored algorithms informing generative AI reflect dominant systems of knowing and being. It is, however, a testament to the existence of coloniality within AI and AI algorithms which (re)produce gendered, racist and xenophobic representations of racialized and minoritized peoples.

Although there is some hope for everyone to influence the datasets that inform algorithms, which in turn might allow for some change, this will not be easy: collaboration will be key and conscientization of everyone on the issues will be as well to address and rectify the issues of problematic algorithms, which are just one tool in a greater system.

Some specific solutions can help by drawing on decolonial thinking that can develop and deepen the understanding of students and educators. This can start with understanding where sites of coloniality replicate harmful generative AI algorithms. Drawing on Mohamed et al. (2020, p. 8)this might include understanding and identifying such sites, which might include where and how algorithms are made and function, who is involved in beta-testing and testing generally, and what local and national policies can be developed. This also includes specifically developing algorithmic literacy as part of digital literacy initiatives (Zembylas, 2023)

Key questions for students/educators

Why do the avatars represent these particular groups in the way that they do?

What, if anything, do the representations get right?

What, if anything, do the illustrations get wrong?

How are the representations problematic?

Where representations are problematic...

What message does this send to someone without knowledge of the context?

What message does this create about the people/cultures/objects portrayed in the images?

What can you do to ensure generative AI creates, if it is possible, more accurate and equitable representations of peoples/cultures/objects?

References

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity Press.

Bowdre, K. M. (2006). Racial mythologies: African American female images and *representation from minstrelsy to the studio era. [Doctoral dissertation/thesis, University of Southern California].

Coalson, R. (2023). Russia’s 2021 Census Results Raise Red Flags Among Experts And Ethnic-Minority Activists – RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2023-07-24 from https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-census-ethnic-minorities-undercounted/32256506.html

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43, No. 6, 1241-1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Dowling, T. (2016, Tuesday, 13 September). Order force: the old grammar rule we all obey without realising – The Guardian. Retrieved 2023-07-24 from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/sep/13/sentence-order-adjectives-rule-elements-of-eloquence-dictionary

Downing, C. (2007). “Interlocking oppressions of sisterhood: (re) presenting the black woman in nineteenth century blackface minstrelsy”. Senior Scholar Papers, Paper 539. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars/539

Fitzgerald, K. J. (2020). Recognizing Race and Ethnicity: Power, Privilege and Inequality (Third ed.). Routledge.

Grosfoguel, R. (2016). What is Racism. Journal of World-Systems Research, 22(1), 9-15. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2016.609

Hill Collins, P. (2019). Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory. Duke University Press.

hooks, b. (2015). Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. Routledge.

King, J. E. (2019). Staying Human: Forty Years of Black Studies Practical-Critical Activity in the Spirit of (Aunt) Jemima. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies - Multi-, Inter- and Transdisciplinarity, 14(2), 9-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/18186874.2019.1690399

Mohamed, S., Png, M.-T., & Isaac, W. (2020). Decolonial AI: Decolonial Theory as Sociotechnical Foresight in Artificial Intelligence. Philosophy & Technology, 33(4), 659-684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-020-00405-8

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2015). Decoloniality as the Future of Africa. History Compass, 13(10), 485-496. https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12264

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York University Press.

Quijano, A., & Ennis, M. (2000). Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South, 1(3), 533-580.

Shadrina, A. (2022). Enacting the babushka: older Russian women ‘doing’ age, gender and class by accepting the role of a stoic carer. Ageing and Society, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0144686x2200037x

Thompson Moore, K. (2021). The Wench: Black Women in the Antebellum Minstrel Show and Popular Culture. The Journal of American Culture, 44(4), 318-335. https://doi.org/10.1111/jacc.13299

Utrata, J. (2008). Babushki as Surrogate Wives: How Single Mothers and Grandmothers Negotiate the Division of Labor in Russia. UC Berkeley: Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3b18d2p8

Wallace-Sanders, K. (2008). Mammy: A century of race, gender, and southern memory. University of Michigan Press.

Wynter, S. (2003). Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument. CR: The New Centennial Review, 3(3), 257-337. https://doi.org/10.2307/41949874

Zembylas, M. (2023). A decolonial approach to AI in higher education teaching and learning: strategies for undoing the ethics of digital neocolonialism. Learning, Media and Technology, 48(1), 25-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.2010094

Creating a student induction with ChatGPT: what it does and misses

ChatGPT seems to be all the rage at the moment, and has been so since at least November/December of 2022. Students and educators are simultaneously worried, excited and fearful of the possibilities that a tool like ChatGPT might create. The inspiration for this post comes from a lot of thinking since at least February and March of this year, coupled with a couple of insightful blog posts from a colleague Dr Emily Nordmann.

What is ChatGPT?

Photo by Tim Mossholder on Pexels.com

I won't labor the point as this has already been talked about in many places, many times over the last few months. In my own words, ChatGPT a tool that draws upon a large set of information that is out there on the web while constantly being trained by its users to finesse what it produces for its users. Depending on whether you use the free or paid version, this information goes back to either 2021 at the time of this writing, or up to now when using the paid version.

The knowledge that ChatGPT draws on is shaped by a mixture of key factors that you should understand:

those who created the ChatGPT AI model - i.e. the programmers

the openly available information that ChatGPT is drawing from

the users whose queries and questions are training ChatGPT, in essence, to become better at what it is doing

Specific knowledge frames outputs

Understanding both what knowledge and whose knowledge informs ChatGPT, and any other tool, is important. When we lift the lid on such tools, we deepen our own understanding of how they work on multiple levels. This then allows us to understand how tools like ChatGPT might (and probably will) create potential omissions, erasures and bias in the knowledge that such tools produce.

With this in mind, I encourage you to try and test out such tools while also asking yourself:

Who has created this tool?

Where are they from?

What are their motivations?

What knowledge is this tool drawing on?

Whose knowledge is this tool drawing on?

What knowledge is missing? And why is it missing?

An example in practice: creating a student induction

Photo by DLKR on Pexels.com

I chose the image above to represent the first prompt and example. What you ask of a large language model like ChatGPT will directly influence the example answer you receive. So, the more vague your question is, the more encompassing the response you will receive.

For a practical example, I decided to get ChatGPT to create a student induction. I choose this example for a few reasons:

to understand what the tool will create using my question prompts

to share with educators an example of a student induction created by ChatGPT

to determine what could be missing from the example that ChatGPT creates

Initial prompt and first output

Below is what ChatGPT created from the initial prompt.

Me: Can you help me to create an induction program for first year students at a university?

ChatGPT: Absolutely, I'd be happy to help you design an induction program for first year university students. Here's a basic outline you could consider:

1. Welcome and Introduction (Day 1)

Welcome Speech: The head of the university or a senior faculty member can begin by welcoming the new students.

Introduction to University: Give an overview of the university's history, ethos, academic structures, key personnel, campus culture, and student life.

2. University Overview (Day 1 - Day 2)

Academic Session: Detail about the course curriculum, academic calendar, grading system, internships, research opportunities, and expectations.

Campus Tour: This could be conducted by senior students. Show important locations like lecture halls, library, labs, student support services, sports facilities, canteens, etc.

Introduction to Faculty: Introduce the teaching and administrative staff. This could be done departmentally.

Workshop on the University's Digital Infrastructure: Train students on how to use the university's website, student portal, learning management system, library resources, etc.

3. Student Services and Support (Day 3)

Presentation from Student Services: Discuss available services like counselling, career guidance, health, accommodation, international student services, etc.

Safety Briefing: Include information about campus safety, emergency services, important contact numbers, and any apps or systems used to enhance student safety.

Presentation from Financial Aid: Discuss scholarships, grants, loans, work-study opportunities, and other financial assistance available.

Presentation from Student Clubs: Representatives from various clubs and societies can introduce their activities.

4. Skills Workshops (Day 4 - Day 5)

Study Skills: Sessions on time management, effective study techniques, research skills, and academic writing.

Soft Skills: Workshops on communication skills, presentation skills, leadership, teamwork, etc.

Personal Development: Sessions on mental health awareness, stress management, maintaining a balanced lifestyle, etc.

5. Social Activities (Throughout the Week)

Ice Breakers and Team Building Activities: To help students get to know each other.

Welcome Party: A casual social event.

Quiz Night: A fun trivia night with questions about the university and general knowledge.

City Tour: For universities in or near cities, a tour of important city landmarks could be helpful.

Meet and Greet with Seniors: Casual interaction sessions with second-year students or student mentors.

6. Reflection and Feedback (End of the Week)

Reflection Session: Allow students to share their experiences and feelings about the first week.

Feedback Collection: Collect feedback about the induction program to improve future iterations.

Please note that this is a general schedule and might need adjustments according to the specific needs of your university and student population. The key is to provide essential information, introduce students to support services, foster community-building, and address any initial worries or concerns students may have.

ChatGPT will often end examples with a little statement like this

Some reflections

As we can see, this is a very detailed student induction for a week-long induction. My question was not specific and therefore the example it produced was broad and encompassing. The example likely draws on a range of university inductions for Year 1 students entering university from across the Internet. However, as we can see, the example is based upon a university that probably has stable electricity, Internet access and good facilities. It is a department within a university that is probably concerned with its reputation and so it takes strides to ensure the students get the best experience (services) possible.

Getting (more) specific

Photo by Lukas on Pexels.com

I wanted to understand how ChatGPT might compress or summarize the previous request. The aim was to understand what might change as a result.

This is only an example and I do not recommend a single day student induction!

Me: Thank you, can you regenerate this but for a 1 day program?ChatGPT

ChatGPT: Certainly, condensing the induction program into one day will require some adjustment, but it's still achievable. Here's a simplified structure:

1. Morning Session: Welcome and University Overview (9:00am - 12:00pm)

Welcome Address: The head of the university or a senior faculty member can begin by welcoming the new students (9:00am - 9:30am).

University Overview: A brief overview of the university's history, ethos, academic structure, key personnel, and student life (9:30am - 10:00am).

Academic Session: Detail about the course curriculum, academic calendar, grading system, and expectations (10:00am - 10:30am).

Short Break (10:30am - 10:45am)

Quick Campus Tour: Highlight the most important locations such as lecture halls, libraries, and student support services. This could be a virtual tour, if needed (10:45am - 11:30am).

Introduction to Faculty: A quick introduction to key faculty members and administrative staff (11:30am - 12:00pm).

2. Afternoon Session: Student Services and Workshops (1:00pm - 4:00pm)

Lunch Break (12:00pm - 1:00pm)

Presentation from Student Services: Highlight the main services like counseling, health, accommodation, etc. (1:00pm - 1:30pm).

Workshop on University's Digital Infrastructure: Train students on how to use the university's website, student portal, learning management system, etc. (1:30pm - 2:00pm).

Short Break (2:00pm - 2:15pm)

Essential Skills Workshop: A condensed workshop on essential academic skills like time management, effective study techniques, and academic writing (2:15pm - 3:00pm).

Safety Briefing: Share information about campus safety, emergency services, and important contact numbers (3:00pm - 3:30pm).

Q&A Session: Allow students to ask any remaining questions they might have (3:30pm - 4:00pm).

3. Evening Session: Social Activity and Close (4:00pm - 6:00pm)

Social Mixer: A casual event where students can interact with each other and faculty members. This could include light refreshments, ice breakers, or team building activities (4:00pm - 5:30pm).

Closing Address: A brief closing note from a senior member of the university staff, encouraging students to make the most of their time at the university (5:30pm - 6:00pm).

Remember, the aim is to provide essential information, help students feel comfortable in their new environment, and foster a sense of community. Be sure to let students know where they can find more detailed information or support if needed.

ChatGPT's disclaimer

Reflections on the details

When I saw this example, I was surprised and left wondering. What surprised me was the time that ChatGPT allocated to such sessions. This would be a highly regimented and time poor induction!

While the overall plan isn't bad, we know from practice that inductions can take a lot longer and might have unexpected events that just happen. Students and staff can get lost along the way, people might cancel and rooms might suddenly be unavailable due to unforeseen circumstances.

Testing ChatGPT for basic biases

Photo by Marta Nogueira on Pexels.com

I went one step further by asking ChatGPT what might be some good dedicated social media platforms for fostering community among the students. The idea is that these could be spaces where students connect pre-arrival. However, there were some problems in the examples that ChatGPT produced.

Here are some of the examples it suggested:

Facebook

WhatsApp

Discord

Slack

Instagram

LinkedIn

Twitter

Microsoft Teams or Google Workspace

Reddit

Clubhouse

SnapChat

TikTok

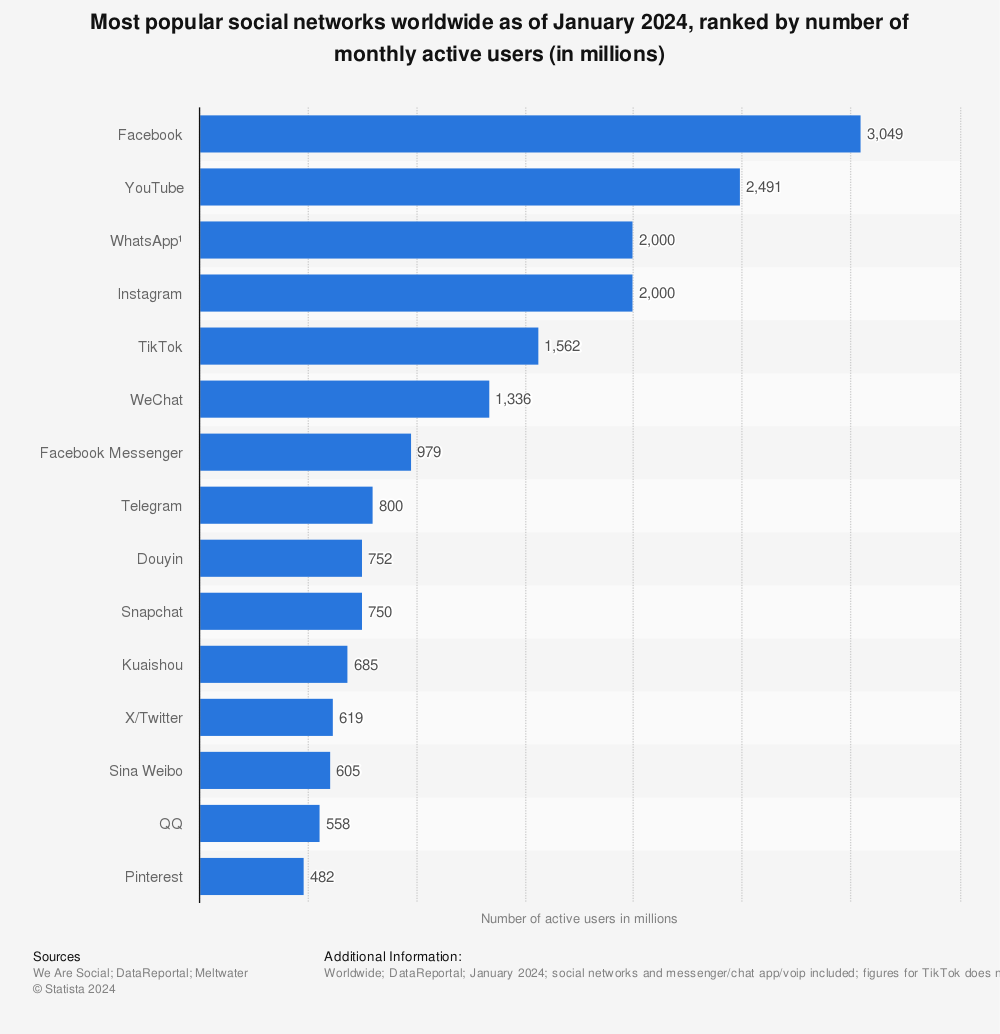

Perhaps the biggest problem with these examples is that they are all very popular and widely used in the West and perhaps particularly in the Anglophone and European West. However, to what extent is this inclusive of those from other regions of the world?

I had to prompt ChatGPT to get it to consider using Telegram and WeChat. For context, Telegram is popular in eastern Europe and the Middle East while WeChat is particularly popular in China and other parts of Asia. The graphic below provides one picture of how some suggestions that ChatGPT are perhaps good ones while others are missing.

Find more statistics at Statista

Closing thoughts

What does this all mean for students and educators? I think it means that we need to do what we can and should be doing: when we use a tool, we should question critically who made it, what its purpose is and what it can and can't do. We should practice it, get to know it and see how well it works. Finally, we should question the information it is generating and be mindful of what is omitted and why it is missing.

For further information...

There are a lot of voices out there who are discussing ChatGPT and all of its potential. The two I have found most useful are those who have been consistent and have provided regular examples, while also creating space for dialogue.

One of the most consistent voices on the uses of ChatGPT on Twitter has been Mushtaq Bilaland one of the most regular organizers of voices has been Phil Anthony from the University of Kent who organizes regular Digitally Enhanced EducationWebinars.

Potential theoretical frameworks

The resource below is from AdvancedHE Pedagogies of Internationalisation theoretical frameworks. These are various theoretical frameworks that can be used for far more than internationalisation for questions and issues related to, for example, critically reflective professional practice, education policy, education futures and many others. Thanks to Sara for finding this one! I've slightly modified the formatting to the original source.

The resource below is from AdvancedHE Pedagogies of Internationalisation theoretical frameworks. It's meant to give a bird's eye of what there is to choose from. These are various theoretical frameworks that can be used for far more than internationalisation for questions and issues related to, for example, critically reflective professional practice, education policy, education futures and many others.

Thanks to Sara for finding this one! I've slightly modified the formatting to the original source.

Theoretical frameworks are essential for guiding research about international students and framing their experiences away from deficit narratives. We’ve compiled here a list of potential theoretical frameworks for research with international students that researchers might consider, along with suggested readings to get you started with learning about them.

Please note this list is still a work in progress and is not fully comprehensive. We welcome any suggested additions.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

AdvancedHE Pedagogies of Internationalisation.

Theories about international students’ transitions and broader experiences

Theory

Purposefully over-simplified description

Suggested reading(s)

Ecological systems theory

The multiple environmental and social systems that impact on an individuals’ experiences

Original: Bronfenbrenner, 1979

Further conceptualisation in higher education: Jones, 2017

Example in practice: Elliot et al., 2016

Multidimensional transition theory

The multilayered academic, social, and emotional transitions that individuals encounter when moving from one space to another

Introduction: Jindal-Snape & Ingram, 2013

Example in practice: Jindal-Snape & Rienties, 2016

Academic resilience theory

Students’ capacity to adapt and develop under uncertainty or adversity

One approach: Holdsworth et al., 2017

Example in practice: Singh, 2021

Rhizomatic transitions

Construction of students’ transitions experiences away from linear pathways towards more fluid, ongoing experiences

Original: Deleuze & Guatarri, 1987

Further conceptualisation in higher education: Gravett, 2019

Example in practice: Balloo et al., 2021

Student engagement model

Model of factors that impact students’ university retention and success

Original: Tinto (1975)

Example in practice: Rienties et al. (2012)

Liminality

Transitional space that may lead to disorientation or ambiguity

Original: Turner, 1969

Example in practice: Parker et al., 2010

Theories about identity development and the self

Theory

Purposefully over-simplified description

Suggested reading(s)

Student agency theory

Students’ capacity to make choices within the constraints of their lived realities

One approach: Biesta & Tedder, 2007

Example in practice: Tran & Vu, 2016

Identity theory

The construction of the self through interactions with experiences and culture

One approach: Hall, 1996

Example in practice: Pham & Saltmarsh, 2013

Capability approach

Theory that people achieve well-being through their capabilities to be and do what they value

One approach: Nussbaum, 2011

Second approach: Sen, 1973; Sen, 1995

Example in practice: Fakunle, 2020

Possible selves

Approach to understanding individuals’ imagined ‘like-to-be’ and ‘like-to-avoid’ futures

Original: Markus & Nurius, 1986

Application to higher education: Harrison, 2018; Henderson et al., 2019

Example in practice: Yang & Noels, 2013

Intersectional theory

Framework for understanding how a person’s multiple identities lead to different forms of oppression and discrimination

Original: Crenshaw, 1989

Example in practice: Forbes-Mewett & McColloch, 2015

Critical race theory

Recognition of race as a social construct and that social structures are inherently racist

Starting point: McCoy, 2015

Example in practice: Yao et al. (2018)

Gendered racialisation

The intersecting identities of gender and race

Original: Selod (2018)

Example in practice: Karaman & Christian (2020)

Theories about intercultural friendships / relationships

Theory

Purposefully over-simplified description

Suggested reading(s)

Intercultural friendship framework

Framework for understanding how intercultural friendships develop on higher education campuses

Kudo et al., 2019

Intergroup contact theory

Theory that biases and prejudices can be minimized through positive contact with people from different outgroups

Original: Allport, 1954

More modern introduction: Dovidio et al., 2005

Meta-analysis: Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006

Intergroup threat theory

Theory that encounters between individuals from different backgrounds can lead to discomforts or threatening feelings

Original: Stephen & Stephen, 2000

Example in practice: Harrison & Peacock, 2013

Theories about pedagogies with international students

Theory

Purposefully over-simplified description

Suggested reading(s)

Critical pedagogies

Application of critical theory to education; philosophy of education that focuses on issues of social justice, power imbalances, and domination

Originals: Freire, 1970; Giroux, 2011

Linked to international students: Khalideen, 2015

Engaged pedagogy

Critical pedagogy approach that values relationships between student / teacher, teacher self-actualisation, humanistic approaches to education

Original: hooks, 1994

Linked to international students: Madge et al., 2009

Academic hospitality

Reflection on academic staff as ‘hosts’ to reciprocally support students as ‘guests’

Original: Bennett, 2000

Further conceptualisation: Ploner, 2018

Bernstein’s pedagogic devices

Theory focusing on the ways pedagogies represent symbolic control over knowledge

Original: Bernstein, 2000

Example in practice: Zeegers & Barron, 2008

Transformative learning

Evaluation of past experience through the acquisition of new knowledge

Original: Mezirow, 1991

Example in practice: Nada et al., 2018; López Murillo, 2021

Theories about international students and the curriculum

Theory

Purposefully over-simplified description

Suggested reading(s)

Hidden curriculum

The unwritten lessons learned about normative values, beliefs, ethics, etc. as a result of educational provisions and settings

Starting point: Apple, 1989

Example in practice: Kidman et al., 2017

Internationalisation of the curriculum

Inclusion of international or intercultural elements into the content and delivery of education

Starting point: Leask, 2015

Further theorisation: Clifford & Montgomery, 2017

Example in practice: Vishwanath & Mummery, 2018

Glocalisation

The blending of global and local elements in the curriculum

Starting point: Robertson, 1994

Further theorisation in higher education: Patel & Lynch, 2013

Tourist gaze

Approach to learning about other cultures as a ‘guest’ or ‘tourist’

Starting point: Urry & Larsen, 2011

Example in practice: Vinall & Shin, 2019

Social learning theories

Theory

Purposefully over-simplified description

Suggested reading(s)

Communities of practice

A set of people who share a common interest or practice

Original: Wenger, 1998

Example in practice: Montgomery & McDowell, 2008

Figured worlds

Development of the self in relation to the social types in their surrounding world

Original: Holland et al., 2001

Example in practice: Chang et al., 2017

Cultural historical activity theory (CHAT)

Relationship between the mind and action within an individual’s situated social world

Original: Engestrom, 2001

Example in practice: Straker, 2016

Sociological theories

Theory

Purposefully over-simplified description

Suggested reading(s)

Bourdieusian theory

Set of thinking tools for investigating power and the way it impacts individuals and societies through structural constraints

Original: Bourdieu, 1979

Helpful guide: Grenfell, 2013

Example in practice: Xu, 2017

Foucauldian theory

Set of thinking tools for investigating power relationships in society, including how they influence language or practice

Original: Foucault, 1977; Foucault, 1972

Helpful guide: Ball, 2013

Example in practice: Koehne, 2006

Gramscian theory

Theory of cultural hegemony – how the state and high economic class use institutions to maintain power

Original: Gramsci, 1971

Helpful guide: Mayo, 2015

Example in practice: Kim, 2011

Decolonial / postcolonial theories

Theory

Purposefully over-simplified description

Suggested reading(s)

Orientalism

Negative portrayals and ‘othering’ of ‘the East’ by ‘the West’ which serve to maintain colonial power and assumed superiority

Original: Edward Said, 1978