Moving to digital education

The purpose of this post is to shed some light on some thoughts to consider, good practices and tips for moving from face-to-face teaching to digital education.NB: These are suggestions to help you to move to digital education. These solutions depend on your own abilities, desire and time. You have the support of your colleagues both in-intuition and beyond – you only need ask. The solutions here are informed suggestions.No perfect solutions exist.

The purpose of this document is to shed some light on some thoughts to consider, good practices and tips for moving from face-to-face teaching to digital education.

The impetus for sharing these ideas comes in light of the spread of the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, which has reached the status of a pandemic on Wednesday, 11 March 2020. Various countries reacted in different ways. As of the time of writing this document, several UK universities (London School of Economics, Durham University, University College London, Lancaster University and Glasgow University) have suspended classroom-based teaching effective either immediately or from Monday, 16 March. More universities are expected to follow the steps of other schools, colleges and universities that have already taken steps in other countries.

NB: These are suggestions to help you to move to digital education. These solutions depend on your own abilities, desire and time. You have the support of your colleagues both in-intuition and beyond – you only need ask. The solutions here are informed suggestions.

No perfect solutions exist.

NB: I may update sections of this post in the coming days as developments take place.

Developing pedagogy for digital delivery & communities of practice

There are a lot of networks out there that are discussing this right now.

One of those networks is on Twitter and you can find out more by following the Learning & Teaching in Higher Education Chat by looking for #LTHEChat and/or by visiting the following link: https://lthechat.com/2020/03/11/covid19-special-edition/ or by following @LTHEChat on Twitter.

Due to the impact of the coronavirus COVID-19, there is a daily chat on Twitter where you can meet and network with colleagues from across HE who are facing the same issues as you. In addition, you’ll also find a lot of ideas directly related to pedagogy, learning and teaching.

Pandemic Pedagogy

Another space that has sprung up is a large, interdisciplinary community on Facebook called Pandemic Pedagogy that has nearly 15,000 members and is constantly growing. You'll meet colleagues from almost every discipline that universities tend to offer.

Considering this group was set up on Thursday, 12 March, it's very quickly becoming a space for educators especially within higher education to ask questions and get and offer solutions on a grand scale.

NB: you will need to request to join but this should be approved within an hour or so!

My own take: This is highly relevant and we should maybe think of this while transitioning our teaching. Things won't be picture perfect and we'll be learning as we go!

Repurposing existing content – thoughts to consider

Review what content you have; if this is video content such as a pre-recording lecture that was captured earlier, ask yourself:

- What, if any, improvements need to be made?

- Is the content still relevant? Do parts of it require an update?

- What needs to be cut/curtailed?

- Can you tolerate sitting through this content for an extended period of time?

As an example of this, if your content has been recorded through lecture capture software you might have to consider the following:

- does the content have good audiovisual quality, or will this impair the learning experience for students?

What to do with existing slide decks from presentations?

Some of you may have a slide deck that has slowly grown over the last few terms or semesters that have become potentially invaluable teaching tools. It's tempting to take an existing slide deck and place it online without any changes as this might be considered a path of least resistance.

However, even with your voiceover and a recorded video, students might benefit from a bit of structure that neatly breaks down the content. If we refer back to our earlier principles, we need to consider relevance and timeliness. So, when we look at a giant slide deck we've prepared over the years, we should reflect and ask ourselves:

- How much of the content is suitable for this particular course or module?

- What needs to be cut?

- What can I do to make the content more engaging and/or interactive for the students?

Solution: Repurposing existing slide decks

One way of taking a slide deck and making it more engaging is to neatly divide content into easily digestible sections; most good slide decks will have a clear enough structure that this won't present an issue.

The next step is to insert an activity slide or two that gets students to think about the issue, problem, or topic at hand by constructing a task or problem for students to consider, process and/or solve in a meaningful way that helps connect what they've learned to practice.

The activity slide(s) can then be followed up by a worked-out solution (or more, depending upon the subject) that looks at the different solutions and provides some commentary/analysis that break the solutions down.

Of course, adding an activity slide and solution will take some time and this is perhaps a drawback. The advantages, however, are numerous: you will have created a reusable learning resource that students can use to learn, apply, practice and check their learning. Whether or not they do this is a different question!

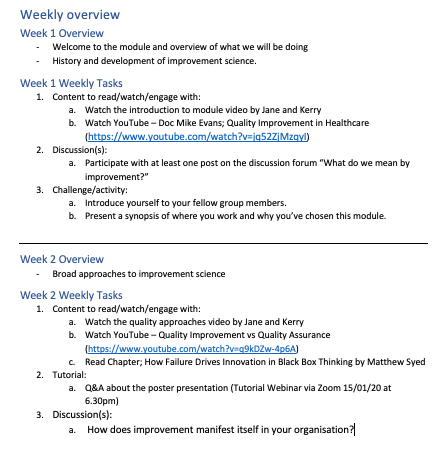

How to structure content for effective delivery online

Structuring online learning and teaching is absolutely key to a successful experience for all stakeholders. Although it may seem obvious, since a significant part of learning online takes place without a teacher/lecturer in the room, students must be shown the path(s) to learning in an explicit manner. This path must be shown within the course/module handbook and through a mixture of audiovisual and visual signposting within a virtual learning environment, such as Moodle.

One way of creating an effective design for learning is to include, at the very least either a video or audio recording that introduces the module/course in brief. A recording of about 5 minutes should generally suffice. The message is best if it's clear, succinct and on point.

Developing netiquette & nurturing a community of online learners

Learning online often entails an increase in text-based communications. In 2020, with a lot of text-based communication already happening via WhatsApp, iMessages and other apps, understanding how to author written messages in an understandable, diplomatic manner is as important as ever.

Therefore, netiquette and how to communicate effectively in text when no visual or body language clues are present is important. This link gives a brief guide on developing good netiquette: https://sway.office.com/ObLxmwHTMKZE4vRB?ref=Link

As far as developing a community of online learners, the link in the post below by Sarah Honeychurch neatly encapsulates a few good thoughts and practices of how to do this. There are a few points to consider when fostering a community of online learners - have a read in the link below!

What to do with seminars?

Although lecture sessions may be recorded and previously recorded lectures may be archived, some of you may be thinking about how you will have seminars.

Seminars are where students get more personal, face-to-face contact with peers and their instructors as these offer an opportunity to discuss, analyze and operationalize concepts and ideas presented during the lectures. There are a few potentially actionable and valuable solutions with the main drawbacks relating to Internet connectivity and access to devices.

Hosting digital seminars

Live seminars can be conducted through using web conferencing software such as Microsoft Teams, Zoom or Google Hangouts. Think of your digital seminars as webinars for your students. If your students already work in small groups, then they could form their own private chats to discuss ideas during the seminar.

Questions prior to moving to digital seminars

- What type of connectivity do your learners have access to?

- What can be pre-recorded?

- What can be broken down into smaller bites?

- What interactivity can be built in?

- Worried about video size? Handbrake (https://handbrake.fr/) can help to shirk file sizes while maintaining audio-visual quality

- What would be best delivered live?

- What do we want students to work on together – regardless of when the learning takes place?

- What type of discussions do we want?

- Asynchronous vs synchronous?

- What technical tools do we have at our disposal?

- PowerPoint presentations – recorded with audio

- Presenting via Teams – and having this recorded

- Collaborative documents for team-based group work

- Invite specific members into each group-specific collaborative document

Practicalities

- You can schedule an online meeting in Teams that will allow your learners to join a digital seminar – make sure that you invite them or send them a link!

- You can record a meeting in Teams by using the red record button, and this will allow others to take part in part of the session and catch up if they weren’t able to attend.

- Make sure that you lay out expectations:

- Have all learners downloaded and signed into Teams successfully?

- Have learners had a chance to ‘get to know’ and play with Teams?

- Do you want students to mute their microphones?

- Do you aim to have a member of each group participate and/or represent their group?

Tips on good practice for online seminars

These tips below were kindly shared by a couple of colleagues I work with - Emma Watton and Florian Bauer:

- Make a note of key messages in advance to give attendees a clear direction of where the webinar is going;

- Keep sentences short and avoid jargon;

- Use slides/diagrams/models to help communicate ideas;

- Signpost to follow up web content/reading etc.;

- Use a booster plug-in speaker if available to improve sound quality, book a room if your office is by the building works;

- Consider a guest joining on a webinar to add different perspectives;

- Be mindful of the length, 10 minutes is a lot of content to listen to online so create more shorter webinars rather than one long one;

- Don’t wear heavily patterned/checked clothing as this can cause pixellation on the screen especially for slower connections;

- Request students to mute their own microphones when they aren't speaking to reduce feedback caused by mics.

Meme shared by a friend.

Remember: when you're joining a web conferencing video, especially if you'll be speaking, take a moment to adjust your web camera and the level of your seat height. Don't sit too close to the web camera and make sure the lighting is decent!

Traditional online discussions

One simple way of creating a longer, asynchronous (not live) discussions around content is through the use of online discussions, such as the use of discussion forums on Moodle. You can assign content that students can access prior to engaging in the discussion.

Tips for successful discussion forums:

- Ask open-ended questions that foster critical thinking and analysis

- Ask questions that get students to reflect and relate their learning back to their own unique contexts (where appropriate)

- Avoid yes/no questions

- Yes/no questions can encourage simplistic answering and thinking.

- Set parameters

- what do you expect of students in terms of behavior and responses?

- How often do you want them to post?

- Will you respond to each and every post?

- Don’t expect everyone to participate

- lurkers gain a lot by silently reading what others are posting; these posts can give them food for thought and cause for writing about their own perspectives

Of course, there are tips for students, too. They can get a lot out of discussions in terms of critical thinking, idea development and written communication and abilities development by taking part in online discussions:

- The University of Waterloo offers this quick guide on tips for students.

What to do with exams?

Exams are often held in person in rooms with an invigilator. Exams can be held online with some limited oversight.

Perhaps more importantly, in light of the circumstances, you might wish to ask yourself:

- Have students already met their intended learning outcomes through other tasks? If so, then is an exam still necessary?

- Why is the written exam still necessary?

- What’s the scope for making the exam ‘open book’?

- Can time parameters for exam be flexible?

Online exams – one way to do it

If you have an exam that consist of short or longer text-based answers, multiple choice questions (MCQs) or mathematical equations, then you can re-create this exam using Google Forms, Microsoft Forms or using the Quiz feature in Moodle.

One simple way I’ve recently tested with success is to use a Microsoft Form to replace a traditional, face-to-face exam:

- the exam consisted of relatively short answers of less than 200 words per question;

- each question was assigned a whole-number mark;

- the online version was set to start and finish at specified times;

- the students were required to log in using their normal university login and password which meant that we could identify

Other tips for doing online exams with Microsoft Forms:

- send students the exam link prior to an online exam with clearly set time parameters;

- send students an exam link immediately prior to the exam – and set no time limits;

- build in some leeway which often standard with Moodle exams in other faculties, departments;

Advantages of using Forms for quizzes/exams

- students are required to log in using their university credentials;

- time restrictions can be set to allow for clear start and end dates and times;

- questions and submitted answers will be collated into an Excel spreadsheet for easy marking;

Example of how an exam or quiz looks in Microsoft Forms

Want more information?

To find out more about how to build effective and authentic quizzes and exams, then take a few moments and follow this link that has more information https://education.microsoft.com/en-us/course/ac59d6bc/overview

Summary & kudos

These are just a few suggestions that I decided to add to the ever-growing amount of solutions that people are putting together after reading inspiring posts by Dale Munday and Kyungmee Lee (see below).

Selected ideas, guidance and readings for designing for learning online & communities of practice

- The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) http://udlguidelines.cast.org/

- Approaches to learning design from JISC, UK: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/designing-learning-and-assessment-in-a-digital-age/approaches-to-learning-design

- Designing an online course from Mesa Community College, Arizona, USA: https://ctl.mesacc.edu/teaching/designing-an-online-course/

- Designing and Teaching Online from SkillsCommons.org: http://support.skillscommons.org/showcases/open-courseware/teacher-training/teach-online/

- Theories and Frameworks for Online Learning: Seeking an Integrated Model: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1154117.pdf

- Pandemic Pedagogy: https://www.facebook.com/groups/2528669267346197/

A great piece of research on mental health amongst English language teaching professionals

I recently participated in a study on mental health among English language teaching professionals. The findings have recently been released and I highly recommend that colleagues read the study and its results.Managers within ELT and EAP (English for academic purposes) might benefit from reading the results of the study. Mental health is a serious issue meriting consideration, especially within the worlds of ELT/EAP/TESOL which are often highly money-driven and fertile grounds for mental health issues and problems.One issue that I am particularly interested in is bullying and harassment within the workplace within Higher Education. These two issues are common causes of mental health issues within HE. From my experiences in HE, all of the worst managers I have worked with have been either clueless or purposefully malevolent in fostering a negative atmosphere by engaging in bullying and/or harassing behavior. On balance, all of the best managers and leaders I have worked with in HE have been keenly aware of these issues, the need to address them and the sensitivity and awareness of how to engage with staff who have or suffer mental health issues. So, there is hope!via The Mental Health of English Language Teachers: Research Findings

CMALT portfolio compiled!

I am taking part in a pilot offered by the Association for Learning Technology that aims to support people in obtaining Certified Membership, or CMALT. In order to obtain CMALT, you have to reflect upon your experience to date and how it relates to the dimensions set out within the frameworks of CMALT. These dimensions, in many ways, reflect, compliment and/or match up with those of the HEA.

I have just submitted my portfolio for review and I am happy to say that I've found it a generally rewarding experience as it's allowed me to look back on my past experiences and see how they relate and connect with one another up until now. It's also allowed me to see how I've developed as an educator over time.The best part of it, of course, is submitting it!

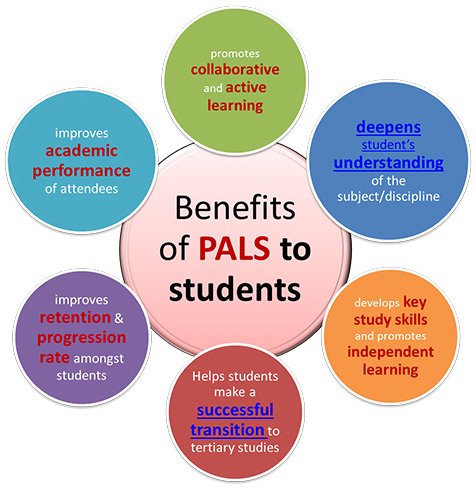

Repost - #15toptips for Student-Centred Teaching 7: Build peer mentoring into your students’ higher education experience

This is a good post about how to build peer mentoring into university courses. With growing numbers of students studying, the value of having experienced students support first-year students is also increasing.Shazia Ahmed and Sarah Honeychurch from the University of Glasgow have also done quite a bit of work on peer assisted learning (PAL), and I've often referred to their research/scholarship when making the case for PAL. One of their latest papers can be found here. Source: #15toptips for Student-Centred Teaching 7: Build peer mentoring into your students’ higher education experience

Ideas on teaching: should we abandon adherence to lesson aims?

Reflections on an article on Bakhtin & digital scholarship

I've recently read an article from the Journal of Applied Social Theory called 'Bakhtin, digital scholarship and new publishing practices as carnival' which discusses how digital scholarship causes disruption to traditional academic practices (Cooper & Condie, 2016). The authors theorize the issues by using Mikhail Bakhtin's concepts on language and dialogue 'to understand how new forms of digital scholarship, particularly blogging and self-publishing' are able to both foster and limit academic dialogues (ibid). One idea throughout the discussion is that of whether digital scholarship represents something 'carnivalesque,' or in other words, something that disrupts traditional, established practices in academia (Bakhtin, 1984b as cited by Cooper & Condie, 2016).

According to the Cooper & Condie (2016), one part of the dominant discourses in academia and research is that these can be viewed as 'finalising' which thus creates a definite, fixed understanding of subjects as opposed to them being viewed as 'unfinalised' and thus changing. Cooper & Condie (ibid) discuss this notion through Bakhtin's view that a more ethical approach to social science is one where research dialogues attempt no finalization of participants in research or topics of inquiry (Frank, 2005 as cited by Cooper & Condie, 2016). Cooper & Condie (ibid) note the example from Bakhtin's analysis of a character called Devushkin from the Dostoevsky novel Poor Folk:

Devushkin, who in recognising himself in another story, did not wish to be represented as ‘something totally quantified, measured, and defined to the last detail: all of you is here, there is nothing more in you, and nothing more to be said about you’ (p. 58). Thus from a Bakhtinian perspective, researchers should not ‘Devushkinise’ their research participants, and the power to finalise people with social science discourses should be scrutinised (Frank, 2005).

In brief, Cooper & Condie (2016) appear to be advocating an 'unfinalised' approach in research that invokes a 'carnivalesque' element is one that seeks to be inclusive by welcoming voices from students, teachers and researchers alike rather than solely established researchers and traditional, established 'norms' within academia.

Traditions in EFL/EAP teaching: the teaching observation

What most interested me about the ideas and theories in the article was the potential applications to teaching within English as a foreign language and English for academic purposes. One tenant of EFL/EAP especially within the UK context is that one should be indoctrinated, as it were, by undertaking the Cambridge CELTA course initially and the Cambridge Delta course subsequently. Indeed, many English language schools and professional organizations, such as BALEAP and the British Council, often require teachers to have one of these qualifications while most UK universities where EFL/EAP is taught often demand the Cambridge Delta qualification which is an expensive and narrowly focused undertaking that does not always fit 'well' within the context of teaching academic writing for university.

Both the Cambridge CELTA and Delta qualifications place a high value on narrow aims for lessons, which must be adhered to in order to demonstrate learning. However, I believe that any experienced teacher would fully understand that a list of 3 aims for the lesson does not indicate learning and will not indicate that the students have learned everything by the end of the lesson. Learning is a continuous process that does not begin and end within the confines of the walls of the classroom. However, those seeking CELTA or Delta qualifications are forced to demonstrate that these fixed aims have been met within the space of 60 minutes, and thus, that learning has been achieved by the students as a result of the teacher's success in addressing and thus ticking off each of the aims!

As part of one's employment as a teacher of English as a foreign language and/or for academic purposes, mandatory observations are often required as part of the contractual obligations, whether employment is in a language school or a university. One set of criteria that observees must note down are the lesson aims. In the observation, the observer will look to these and attempt to identify whether the aims have been met within the context of the lesson plan, often within the space of a 60-90 minute observation.

However, this approach to observations, in my opinion, raises several questions which relate back to the theories in Cooper & Condie's article:

- Can the lesson aims, without a doubt, demonstrate whether learning has taken place after the lesson?

- Do not a series of lesson aims suggest that learning is fixable, and thus able to be finalized?

- Where do student interest and inquiry come into play as far as the lesson aims, and whether these are met or not?

- Where the students and teachers spend more time on specific aims that lead to an aim not being met, should this reflect poorly on the teacher?

A potential solution

I think one potential solution is to revamp how observations are done: they should not be conducted according to how Cambridge CELTA and Delta observed lessons are conducted as these observations are quite narrow in focus and presume that a 60-90 minute 'snapshot' of the teacher is 'enough' to make a value judgement. These observations also tend not to focus on students at all, but solely on the teachers - as if learning and teaching were not a dialogic process! Learning and teaching is a dialogic process - without dialogue, the teacher would become a speaker who talks at the students as opposed to discussing with the students the issues being covered.

Therefore, observations should also look at learning on the part of the students rather than focusing solely on whether the teacher is delivering a lesson and meeting lesson aims according to a plan. A pre-planned lesson on paper might indicate that deviation from the plan should be avoided in order to fulfill the lesson aims and thus the plan. For some reason, lesson aims are traditionally seen as tenants - they must be achieved.

However, learning and teaching in the classroom does not often go according to plan for various reasons. One reason is that students might want to know more about a particular area, and thus might have questions, deep questions, about a particular topic. If we, as teachers, only quickly address their questions on the surface without going into depth in order to meet our aims, I feel we are doing our students a disservice. This also can make teachers appear a bit rushed or hesitant to address students' concerns - within the eyes of the students - at their expense and for achieving the lesson aims, which might negatively affect the atmosphere in the classroom.

Another reason might be that the materials, at times published within a book or within a course pack, might work in theory within the lesson plan and thus within the mind of the teacher but in practice do not work according to plan. In this case, the teacher has to 'teach on their feet' especially they observe that the materials are presenting problems for the students.

Final (but unfinished) thoughts...

To sum up, if learning and teaching is a dialogic process, it is very likely an 'unfinalised' process that does not end once the class has ended. Students do not simply learn everything within the space of 60-120 minutes whether or not lesson aims have been met. Teachers should advocate for different forms of observation in order to reflect the complex reality and nature of learning.

Learning continues through dialogues outside the classroom, whether face-to-face or online through discussion forums or text messaging or most importantly, within the minds of the students. I would argue that learning has no natural endpoint, and thus, it simply cannot be encapsulated or evidenced within a lesson observation.

We can attempt to understand what learning has taken place in the classroom, but in order to do this, observation practices will need to start taking a closer look at the learners perhaps before, during and after a particular lesson. A more 'carnivalesque' approach is merited - one that is inclusive and looks at all participants in the learning and teaching process, and gets a sense of their voices on the processes. A snapshot observation of teachers is old hat, and in the world of the digital - where information can be easily obtained and disseminated to foster and support learning and teaching - I believe such observations are outmoded. A new model for observations must include student learning and participation as they are also key stakeholders in the process of learning and teaching. To close, Bakhtin would not support traditionally accepted notions of teacher observation practices in 21st Century world of teaching English as a foreign language/English for academic purposes, and therefore, change is needed.

Bibliography

Cooper, A., & Condie, J. (2016). Bakhtin, digital scholarship and new publishing practices as carnival. Journal of Applied Social Theory, 1(1). Retrieved from http://socialtheoryapplied.com/journal/jast/article/view/31/7

Designing and Conducting a SoTL Project using a Worksheet: A Baker’s Dozen of Important Sets of Guiding Questions — The SoTL Advocate

I came across this post from another blog that I follow. The post has a few ideas for scholarship and some guiding questions that can help teaching staff identify potential areas for scholarship/research.Read more below at the original post.

Written by Kathleen McKinney, Professor and Cross Chair in SoTL, Illinois State University Many of us have numerous SoTL research topics or questions floating around in our minds. We have multiple ideas for design and measurement. We have thoughts, perhaps concerns, about IRB issues. We may be unsure about multiple methods/measures or whether to obtain […]

Facebook for Peer Assisted Learning

Today I gave a presentation in which I shared scholarship that has been done by Shazia Ahmed, Sarah Honeychurch and Lorna Love from Student Learning Service and the Learning & Teaching Centre of the University of Glasgow on virtual peer assisted learning groups organized on Facebook.

Project background & issues

The groups support first year undergraduate students, and beyond, from a variety of subjects. The Facebook PAL groups have proved to be highly successful, and indeed, the math and statistics support group, sigma, recognized the significance of the contribution that the Facebook PAL groups have made to the field by awarding Shazia and Sarah sigma prize winner for 2014 for Innovation of the Year.The virtual PAL groups have been in operation since 2010 when they were first piloted as a solution to address issues that voluntary, traditional, face-to-face peer assisted learning sessions raised:

- Different timetabling across the subjects and students' own schedules made it difficult to schedule PAL sessions within a typical 0900-1700 working/study day

- Low attendance was more often the norm since PAL sessions were often scheduled outside of the 0900-1700 working day, and as winter approached after the start of the academic year, the days grew shorter, darker and thus students were far less likely to attend voluntary, optional PAL sessions.

- Student had other competing responsibilities (e.g. part-time work, caring responsibilities, commuting and others).

- Traditional PAL sessions were optional whereas tutorials were mandatory. First year undergraduates already face confidence and shyness issues, so attending an optional session was not a priority for them.

- New, first year students lacked of a sense of identity or belonging as many were new to not only the Glasgow area and university, but also the academic community.

Solution

In 2010, staff from the Student Learning Service & Learning and Teaching Centre teams at Glasgow instigated and semi-moderated Facebook groups for Year 1 Maths and Computing students in the first instance, with the aim of:

- Providing a space to encourage interaction and academic dialogue between classmates, senior students and support staff.

- Having students share questions with each other.

- Allowing virtual peer assisted learning sessions to happen spontaneously and asynchronously.

Students would also share resources, ask questions about lectures, labs, the university, etc. and generally support each other and their transition from school to university.

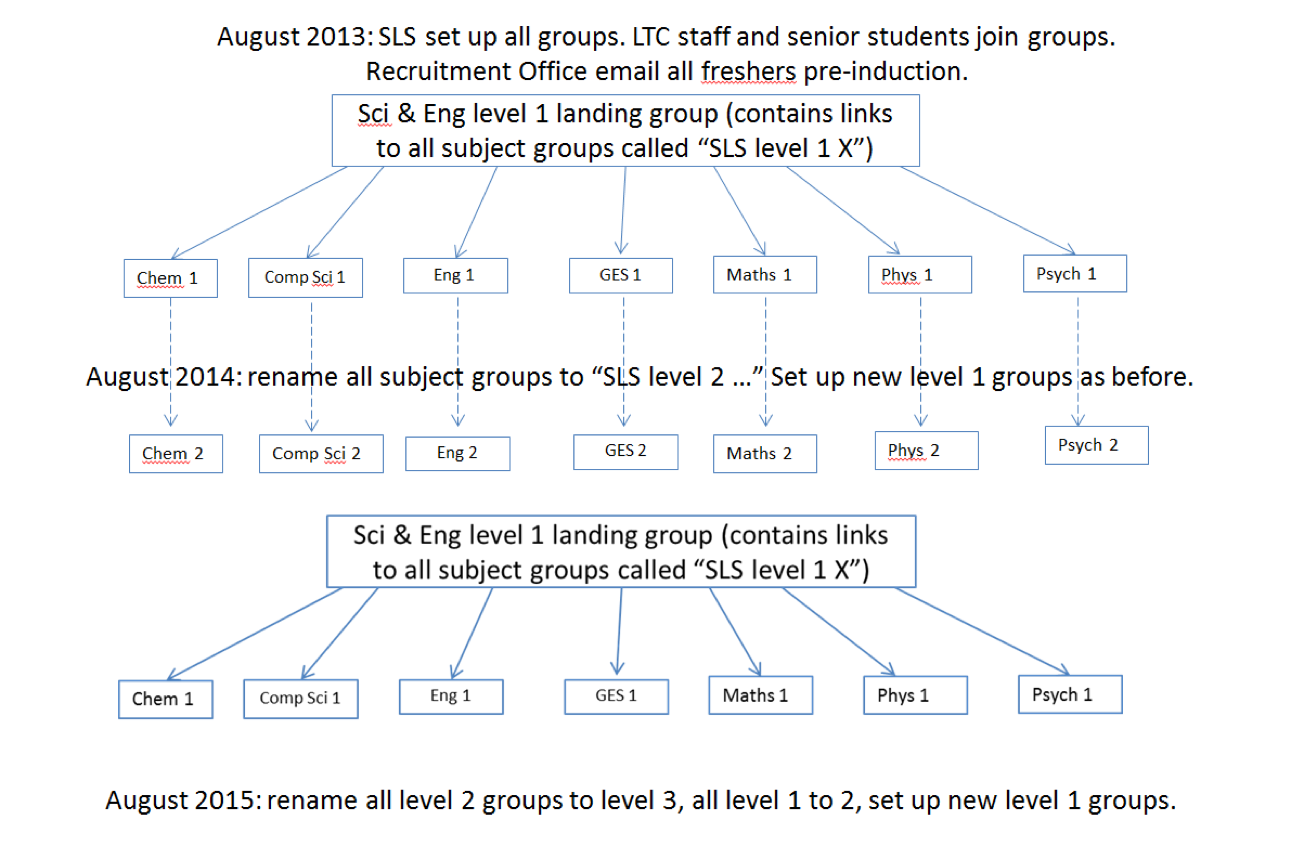

Structure of Facebook PAL groups

Figure 1 below (Ahmed & Honeychurch, 2015) shows how Student Learning Service set up the groups for the College of Science and Engineering at the University of Glasgow. SLS set up a 'landing group' on Facebook with links to respective subject-specific Facebook PAL groups. Students were invited to join via e-mail.Students would first join the landing group and then join their subject group (e.g. Comp Sci 1 for first year computing science). Students would remain members of their subject group throughout the year. In the following academic year, first year groups would be renamed as 'Subject 2' (e.g. Comp Sci 2) and the groups would be rolled over, thus preserving the learning communities that had been formed with the first year undergraduates.

Rationale for Facebook PAL groups

Throughout their scholarship and literature, Lorna, Shazia and Sarah note the following reasons for using Facebook for PAL groups:

- Glasgow University conducts a bi-annual 'digital natives' survey of incoming first year students, and evidence has shown that students do still use Facebook.

- Students can form relationships immediately prior to starting a course, thus smoothening the transition from school to university, and their course.

- Students can obtain support quickly, when they need/want it, and thus this leads to increased student engagement and learning being fostered.

- Learning communities can be formed over a year, and maintained beyond that year.

- Social interactions online can transform into face-to-face interactions, which lead to students organizing and holding face-to-face study sessions when convenient for them.

Lecturers do not maintain a presence within the Facebook PAL groups as their presence can be intimidating, but the presence of academic development/support staff, along with peers (senior students) provides encouragement and support to students in the group.It's worth noting that although apps like WhatsApp and Snapchat are growing in usage and popularity, these are fundamentally different as they are not social networking apps in the same sense as Facebook or Academia.edu.Interestingly, related research on this topic offers further insights into student-led Facebook groups as examples of open educational practices that actually foster educational inclusion, and can help group members in learning to manage their 'emotional reactions, anxieties and stress levels' while improving retention and providing 'just in time' academic support (Coughlan & Perryman, 2015:9)

Concerns & ethical considerations

I communicated with Shazia and Sarah via e-mail on a few occasions and quizzed them about various concerns that I had - just in case! - and they kindly addressed them:

Recruiting/training senior students:

In August I post a message on all the groups with a link to the new Entrants group and just ask the senior students if they would like to join and contribute. It always amazes me how many will volunteer and actively participate. We don’t provide any training.

Plagiarism/collusion:

This has never been an issue. Part of the reason could be that Sarah and I have a presence on the groups and that deters students. Even with ‘simple’ things like first year maths homework whenever students post queries, the classmates or senior students respond with hints and clues as to how the question can be tackled, or sometimes refer students to the relevant section in the notes on Moodle. I have never seen anyone ‘hand over’ an answer.

Interaction and moderation required from academic support staff:

I think you just have to try it and see! The point for us is to promote peer- assisted learning and to create a community so I tend to make more effort to interact with everyone at the beginning of the year to help ‘establish’ the groups, and gradually step back.There are a lot of groups to moderate so it’s difficult to keep an eye on all the conversations – but other students (including older students) are usually quicker to reply than I am anyway! If students are anxious to hear from me or Sarah, they just tag us and we respond to them as quickly as we can.It’s a good idea to have more than one admin in the groups. It’s useful if one admin is unavailable and there are members to add, spammy posts to remove, or posts to pin, etc.

Ethical considerations of using Facebook

Privacy

Of course privacy is an issue that some staff might be concerned about in terms of supporting students within a Facebook peer assisted learning group. This concern is understandable, but luckily, also easily addressable.Staff can manipulate Facebook's privacy settings to ensure that their posts are only seen by their friends. Staff needn't be 'friends' with students in Facebook groups. Indeed, when I queried whether staff were in Facebook groups, many said 'yes'. When I asked whether they were friends with all group members of a Facebook group, many said 'no', and generally this isn't a requirement of being a member of a Facebook group rather it's an added plus if you know someone who's already a member.

Ethical issues of using Facebook

An interesting and valid point came up toward the end of my presentation about the ethical considerations of using Facebook for peer assisted learning groups. The crux of the point made was that Facebook is a for-profit company which makes money off of people, and whether we as academic staff should be asking students to use Facebook for learning and teaching purposes. I did find this to be an interesting point, and it got me thinking of another large for-profit company...Microsoft products are (still) widely used in many higher education establishments. Indeed, universities do pay a certain premium for using Microsoft products, although the Microsoft Office Suite of programs is not nearly as expensive as it used to be.This is despite the fact that Google Apps for Education offer a free suite of products that university students and staff can use (if their university has signed up to a free Google Apps for Education account) that work effectively and efficiently across devices, provide for data and Intellectual Property rights protection, and simply just work and do what users want to do.In short, I appreciate the point about whether it is ethical to ask students to use Facebook for learning and teaching purposes. I think a bit of informal querying of students might reveal that they already use Facebook for study purposes in some respects (e.g. arranging meetings, sharing files en masse and so on), and that they have no problems doing so.I would ask whether it is ethical for Microsoft to make a profit off students, staff and universities who use or have to use its products. Microsoft is a very large company that has embedded itself within business and higher education to a very extensive level, but generally speaking, it does not receive the same level of criticism, as say, Facebook or Google do. Sure, a lot of people do complain about Microsoft products, but interestingly, I have rarely heard anyone question the ethical considerations of using Microsoft products. I suspect this is because Microsoft is embedded, and therefore invisible to such scrutiny.

Benefits of Facebook PAL groups over traditional PAL

There are several key benefits that should seriously be considered as reasons for instigating, trialling and implementing Facebook peer assisted learning groups that Sarah, Shazia and Lorna have observed since 2010:

- Availability:

- Online conversations can take place at any time. Access to peer assisted learning is constant and students don't have to wait for a scheduled session, which is important for students with full academic timetables and/or other commitments. They can get help when they need it.

- Conversations can be easily revisited, and students aren't forced to participate.

- One question asked may lead to several questions being answered simultaneously. In a large cohort (100+ students) this can be quite valuable, as several students are likely to have the same question simultaneously or at (slightly) different stages of an assignment.

- Academic & social skills development:

- Collaborative learning is instigated and co-creation of knowledge is fostered, which lead to learning communities being formed.

- Students develop their written communication skills (e.g. clarity, precision) in that they are forced to use clear language when asking questions of peers.

- Students have to use subject specific terminology, and written conversations online gives students practice of this while getting them to think critically about their language and the terminology usage. A clearly-worded question is likely to garner attention and answers, whereas one that's unclear/poorly worded might not.

- Facilitators (e.g. senior students and academic support staff) act as academic scaffolders who provide clues, hints and links to resources rather than solely provide. For senior students, this helps them develop their mentoring abilities and related skills, for newer students, this can help them to understand that their peers can be good resources better understanding their subject.

- Inclusivity

- Online interaction fosters inclusivity and leads to real world, face-to-face connections and relationships.

- Students whose first language isn’t English appreciate the extra time created by this medium to digest, understand and participate in conversations.

- A more level playing field is created and shy students are more likely to participate.

- Conversations in virtual peer assisted learning extend to all group members rather than just session members. In other words, face-to-face sessions based upon conversation afford a more ephemeral mode of communication unless students/staff are recording and writing down everything that is discussed in a session. As noted above, written conversations can be revisited.

- Scholarship & evidence

- The scholarship that Sarah, Shazia and Lorna have undertaken since 2010 with several hundred students demonstrates that such an approach to peer assisted learning can work and does work. They have provided an easily replicable model that could be set up for any program and within any institution.

References & further reading

Many of the papers and presentations that Shazia, Sarah and Lorna have done can be found at the following links:

- Shazia's Academia.edu profile: https://glasgow.academia.edu/ShaziaAhmed

- Sarah's Academia.edu profile: https://glasgow.academia.edu/SarahHoneychurch

- Lorna's Academia.edu profile: https://independent.academia.edu/LoveLorna

Ahmed, S., and Honeychurch, S. (2015) Using social media to promote deep learning and increase student engagement in the college of science & engineering. In: IMA International Conference on Barriers and Enablers to Learning Maths: Enhancing Learning and Teaching for All Learners, Glasgow, Scotland, 10-12 Jun 2015.Coughlan, T. and Perryman, L. (2015) Are student-led Facebook groups open educational practices? In: OER15, 14-15 April 2015, Cardiff. Available at http://oro.open.ac.uk/42541/4/OER15.pdf.Love, L., Ahmed, S., and Honeychurch, S. (2013) Social media for student learning: enhancing the student experience and promoting deep learning. In: Enhancement and Innovation in Education, Glasgow, UK, 11-13 Jun 2013.

Notes on 'How we answer the questions'

Event overview

I attended an event called 'How we answer the questions' on the ALDinHE mailing list and though that it would be a good event to attend in order to get insight into how staff at other programmes address the issues related to questions that students bring to tutorials and also for me to better understand what kind of materials and provision exist for students elsewhere. The one-day event was hosted by the welcoming staff of The University of Manchester's Library and those who work on the skills programme My Learning Essentials. So, I went up to Manchester the evening before and stayed overnight and the next morning I walked from where I was staying along Canal Street through Manchester Met University to reach the University of Manchester. They both appear to sit right next to each other, and have very large campuses.The agenda for the day had a focus set out by the convenors but would also be participant driven as the convenors invited people to share why they had come. The attendees gave the following reasons...

- To bring in new ideas and experience

- To establish the scope of support

- To find out how others do it

- To gain confidence in their own programmes and provisions

- To identifying hidden needs that students may have

- To find out how to measure/explain impact of de

- And many others…

Images

NB: All images here apart from the one of Bloom's Taxonomy were taken by myself with an Olympus Pen E-PL7.

The setting & direction

The team at the impressive Alan Gilbert Learning Commons has on staff around 20 students that work 8 hours weekly and are involved in many projects that help support staff work but they also work directly with students. The staff receive a lot of questions about issues that are related to pastoral care; the students reach out, and the staff within the center direct the students to resources and people who can provide assistance and support. I quite like the idea of having student employees working with development support staff but also directly with students as this can help legitimize a service the wider student body. One common theme that the convenors noted that is an issue of the times - there are continually shrinking resources, but a constant growing demand for support. Students often ask questions that can be challenging, or as one presenter put it ‘how to catch a goat’!Students also ask 'typical' questions related to referencing - how to do it, how to approach it and so on, even though the Library has a lot of resources related to referencing (e.g. guides, tools and so on). Some questions are easily answered, but others can present a challenge. So, it’s up to tutors to find out what the question really is, how best to answer the question, what to use to answer the question (e.g. what resource or resources, which platform) and how to make the answer/resource available to all. So to this end, in the session we did a lot of idea exchange.

One common theme that the convenors noted that is an issue of the times - there are continually shrinking resources, but a constant growing demand for support. Students often ask questions that can be challenging, or as one presenter put it ‘how to catch a goat’!Students also ask 'typical' questions related to referencing - how to do it, how to approach it and so on, even though the Library has a lot of resources related to referencing (e.g. guides, tools and so on). Some questions are easily answered, but others can present a challenge. So, it’s up to tutors to find out what the question really is, how best to answer the question, what to use to answer the question (e.g. what resource or resources, which platform) and how to make the answer/resource available to all. So to this end, in the session we did a lot of idea exchange.

Sharing ideas (and solutions) through questions

The first activity attendees did was to come up with questions that academic development/library support staff are often asked by students. To do this, we used different colored stickies... Yellow stickie notes - We noted down what questions students ask us but also questions that we can ask ourselves such as...

Yellow stickie notes - We noted down what questions students ask us but also questions that we can ask ourselves such as...

- In terms of academic referencing...

- Students often ask 'How many references do I need?'

- This led us to ask...

- Is a definitive answer needed?

- How many are really needed?

- How long is a piece of string?!

- Some attendees also asked...

- Can we advisors provide a definitive answer to the question of how many references are needed or are sufficient?

- Does the effectiveness of the answer to an essay question outweigh how many references are needed or used?

- Should we learn how to use reference management systems such as Zotero, EndNote, etc?

- Is it okay to just use Google Scholar for researching?

- This led us to ask...

- Students often ask 'How many references do I need?'

- In terms of dissertation writing...

- Students ask...

- What they should do their dissertation on...

- What they should focus on...

- Students ask...

Orange stickie notes - here we talked about potential tools that staff have at their disposal to answer students' questions and queries. In terms of some of the answers...

- Advisors can get students to think about most issues by asking open-ended questions that allow the student to critically consider their response as opposed to yes/no questioning.

- Staff can also make sure there are enough resources to support the student’s investigation and research into a particular topic area. This, of course, might require developing resources (e.g. online resources that could sit within a space like Moodle or YouTube-based mini-guides or tutorials that address some of the most common questions students ask)

- Advisors can also point out perhaps if the area the student has appears too narrow.

- Students sometimes bring their assignment briefs, which spell out to varying degrees the aims of the assignment and what, if any, references are required, and academic development support advisors should exploit these to a great extent.

- Academic writing tutors are very likely to get students to dissect an essay question in order to understand what the question is looking for in terms of scope, relevance and specific aim. However, some staff who do not teach English for academic purposes or who are not subject-specialists might feel uncomfortable exploiting such resources. That said, this presents a space for collaboration between lecturers and library support staff and/or between academic development/learning advisors and lecturers.

- One attendee noted that we can refer students back to lecturers if we don’t feel comfortable with answering a particular question (e.g. precisely how many references are needed, or which specific texts/key sources to refer to…)

- Another member of staff that it is important to make students aware of tools/workshops that are available and/or online resource can sometimes answer students questions, but that staff should be mindful of precisely what the student seeks or is asking.

A third color - we spoke briefly about potential solutions, and the general consensus appeared to be the following

- It's a good idea to have and/or develop resources that staff can refer to students so that they can readily access and exploit these resources in order to find the answers for themselves. At the same time..

- It's a good idea to fully understand what the student seeks before addressing the issue. For example, a student may have signed up to a 1:1 drop-in to ask questions about an essay and s/he may have identified key areas prior to the session that they wished to be address... However, from the time that they signed up until the time that they have arrived at the tutorial, their needs might have changed, and subsequently, a tutor who had prepared for 1, 2 and 3 might now be faced with addressing topics 4, 5 and 6!

- One attendee noted that she would likely address 4, 5 and 6 because the student may well have self-addressed the previously identified areas in the meantime. That way students could get the full benefit of having their needs (even 'lately' identified) rather than the tutor sticking to the initial request.

This first activity wrapped up with one common thought: it can be tough to answer questions due to time constraints, lack of resources and unclarity of questions being asked, however staff should strive to identify the needs of students and address those and/or refer the student to the appropriate person or resource timely manner. In this way, not only will students leave a developmental support session or drop-in feeling as if their question has been answered but this will also help to further legitimize the need for such programmes/services within a university, again, where resources are shrinking but need continues to grow.

Talk 1: Answering the question (when you don’t know the answer!)

This talk was presented by Michael Stevenson a Teaching and Learning Assistant of the Teaching and Learning Team. In brief, it was a talk in which Michael presented how the team their online referral process in order to reduce duplication of support while helping students to get their queries addressed by the right team. To help attendees understand why students might need to be referred, we were given a card that had a scenario. A student had come to a support session and asked how he/she could get a better mark as their friend had gotten a very good mark by using an essay from an essay mill... Given the currency of the topic, attendees came up with the following as possible actions to take:

- Refer student to academic policies;

- Tease out what the student thinks about this in a 1:1 consultation to get them to understand the issues behind using such a service;

- Refer the issue to the academic integrity unit of a university;

- Explain academically why it’s not a good way to approach assignments;

- And others!

The reasoning behind this task was to get attendees to think about the following:

Why should or would awe refer students?

A few reasons were put forth:

- Because we just don’t know the answer but we can find the person who would be able to answer this.

- We kind of know the answer but we know of experts who can better answer than we can.

However, as the speaker noted, students might want a quick answer and time can be pressing. Perhaps our timetables are full, we have a meeting come up or we’ve created resources online that can help students. The speaker noted that staff don’t want to (and shouldn't really) duplicate the effort though. To address this, staff can find out from students what’s been done by trying to clarify what they’ve done and how they’ve done it, and then staff can proceed to source relevant advice and information in order to give them tips and advice on how/what to improve. That said, as earlier noted, students might sign up with specific questions, but then come and ask different questions that they hadn’t identified, which will take further time away from the session and/or put pressure on the advisor to assist in an area that they hadn’t prepared for. In this case, again, it might be a good idea to address their 'new' queries rather than solely addressing the original ones.Michael suggested that learning advisors’ aims might be to fully support student learning and university experience to ensure that they’re getting the most out of their experience while also using the resources available to them in order to provide students with the best support possible that also empowers them to understand how to address their own needs more independently.

The enquiry system process - a project

Michael went on to present the project process that university went through to develop their online student enquiry system that consisted of a few phases. In brief, they first tested out different systems, assessed existing enquiry systems in place used across the university and profiled the users of the enquiry system and routes that students use.Next, Michael and his colleagues consulted with the university project management team to identify what an enquiry actually is defined as in order to ultimately define the scope of enquiries that the team would be tasked with answering. Through this consultation, strengths, areas for improvement and overlap were identified. Using the 'Lean principles' they aimed to limit the 'waste' in the enquiry systems, i.e. they aimed to ensure students' enquiries were answered appropriately in a timely manner that avoided duplication of effort.In terms of concrete steps taken to improve the enquiry system, self-help resources were enhanced by developing and expanding online resources in order to get students to help themselves by providing them with relevant resources that would foster this process and give them guidance and answers that they could source independently.From what I can understand, these resources were then branded as My Learning Essentials so that staff/students would both clearly understand what resources were available online and what to call them as this could help all parties talk about and refer to the same set of tools. Essentially, it is a clearly signposted, named or branded one-stop shop that allows students to source information sought whether through bookable workshops, interactive activities online, which cover everything from essay writing to self-awareness and wellbeing (!), or through scheduled drop-ins. From looking through the resources offered, it seems that what Manchester offers to students sets a good standard for other universities to work towards in terms of the type of support, whether developmental academically or personally, can be developed and provided.

Challenges during the project

Like any project, Michael and his colleagues faced a few challenges. Some of these included... identifying what staff wanted everyone else to know what to know. A strength of trying to understand this was that each member of the team had their own strengths that they brought to the table.Another included understanding enquiry channels used by students. These included and were used to varying degrees:

- Face to face support

- Telephone

- LANDesk - (the online enquiry management system via IT services)

- Library Chat

- This is a live chat tool on the Library homepage; it was not really well used; and it presented difficulties in terms of tracking student usage.

- Social media

- Michael noted that the team uses Twitter, but that the university marketing department/unit has tight control over how this is used.

Per the social media challenge, in my own professional opinion and as someone who has read into the usage of and has used social media for learning and teaching, it could be that the marketing team might not fully understand nor appreciate that a department such as their own should never be solely in control of social media for a several reasons:

- They might be tasked with protecting the brand and thus limiting what information is/isn't disseminated by limiting who can/cannot do this.

- Using social media for student recruitment and disseminating news about a university is one thing, but using social media to develop students' self-awareness as learners and to help them self-regulate their learning is something entirely different and, I would argue, outside the remit of marketing departments unless they are open to working directly with academic support and teaching staff to better understand how social media can be used by learning and teaching staff. There are many opportunities for sharing good practices that marketing specialists can give to teaching staff and vice versa.

- Marketing departments are not always aware of how Twitter or Facebook, for example, can be used for fostering and developing learning and teaching inside and outside of the classroom even though research does clearly indicate that engaging students in the social media that they use can actually lead to an enhanced student experience and ultimately retention.

Other barriers

There were other barriers to referral that were brought up and discussed. These included the issue that staff should think about and consider all the different avenues for support. Staff should seek to understand whether they've answered the questions and provided support to students. Related to this, there should be an understanding of whether staff haven’t been able to address a question and/or refer a question onwards, and the reasons for this.Other barriers were more practical. These included not knowing the expertise of a large team or set of teams who can provide support. Working in a large university can present this issue quite naturally. Another included staffing hours. For example, students ask questions all the time, and might want/expect support outside of core hours. In order to address this, staff can help students to understand what expectations are reasonable in terms of when support can be provided, and when to expect an answer. There was also the issue of boundaries. For example, what are we saying when we always say ‘Yes’ to a student’s call for support? In order to address this, providing a distance learning/online provision for developmental support can allow many of students’ queries to be answered outside of core hours, though this type of provision requires some careful consideration as far as what to include, how to develop such resources and so on. Related to this, students and staff require a knowledge of resources. If students are fully aware of what is available to them in terms of resources offline or online, then their queries might be better addressed and answered in a more timely manner.

Questions from the audience

Throughout the talk, students were referred to as customers which is something that is happening increasingly within discourses in higher education. Some attendees asked whether we should view students as customers because this might change how staff provide their services to students and interact with students. Some other questions related to this then came up:

- Do students view developmental support services as a service, such as those provided in a bank or cafe? In short, are staff supposed to just provide an answer or set of answers, or are staff in place to provide support to students that allow them to develop into autonomous learners who are empowered with the knowledge, skills and tools in order to formulate their path to success?

- Or do students come to these services subconsciously aware of the power dynamics at play - they are asking for assistance or help of others who they may view or hope are experts who can provide developmental support.

- Are the same students asking the same questions multiple times throughout the year? This would be useful to know to help identify a gap in the provision or service.

Talk 2: What if students don’t have a question, but still feel that they need help?

The next talk was presented by Claire Stewart, Library & Academic Adviser, and Sandie Donnelly, a Learning Enhancement Manager, from the University of Cumbria. It generated quite a bit of discussion as it touched upon an issue that, I feel, all academic learning advisors and learning developers face on a regular basis. Some common examples that Claire presented included the following questions about academic writing/writing assignments that students typically raise:

- Can you help me with my essay?

- My tutor told me to come and see you about ....

- [in an e-mail] Please give me feedback on the attached document…

Claire noted that students often don’t feel confident in their work and so their first reaction is to ask for support. She put the question to the audience: How do we as advisers negotiated this type of issue?

A hierarchy of academic writing needs

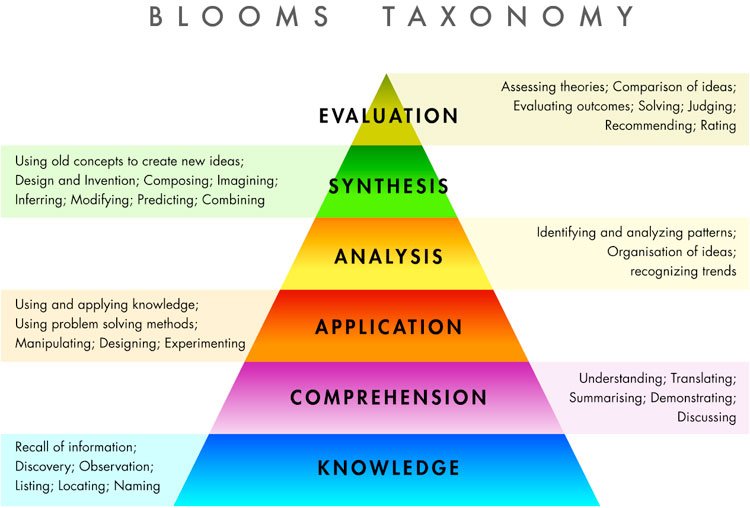

One solution that Claire developed was a hierarchy of academic writing needs from bottom to top, which reminded me a lot of how Bloom's Taxonomy is structured; I've included an image of this from another WordPress blog below.Claire outlines the hierarchy that learning developers could use as follows (from the basis/bottom to the top):

- Comprehension

- Identifying student comprehension of the essay question or task at hand

- Readability

- Looking at sentences, how grammar and language are used and how ideas are expressed (clarity)

- Highlighting issues with these

- Structure

- Looking at paragraphing, overall structure, planning.

- Is there a sensible chain of paragraphs and ideas/logic?

- Is there an intro/conclusion to the essay?

- Use of evidence

- Are students using relevant sources?

- What is the quality of these?

- Do they understand referencing conventions and how to reference?

- Critical analysis

- Is there evidence showing a development of an argument?

- Are they challenging the sources they’re using or merely describing/retelling what sources say?

- Is there a synthesis of sources?

Using the hierarchy

Claire suggested that the hierarchy could be used as a personal strategy to identify problems and prioritize objectives. It also can allow staff to direct students to work directly on the assignment while signposting students to self-help resources based upon the areas for improvement that the learning developer has identified. Another potential benefit of such a tool is that staff can use it to scaffold the development of academic skills over a longer period of time, especially if a student regularly seeks advice.

What does critical analysis mean?

Sandie was the next to present on the issue of criticality in students' writing, which is often a common issue that students from across the disciplines struggle with when completing their assignments. Sandie discussed how...

- Students often say that they put a lot of sources in their essay, but upon submission of a paper they might receive feedback from their lecturer noting that the essay is not critical or critical enough. This can frustrate students who feel that they have done a lot of hard work to include a lot of references within a paper.

- Students ask why lecturers say that they shouldn’t go in depth in describing case studies.

- Students report that they can do a placement and enjoy it but don’t get the critical analysis part of writing it up or considering it.

How can non-subject specialists support students’ development in critical analysis and reflective practice?

To answer this in brief, Sandie highlighted that in fact the student is the subject expert. Learning developers can ask them how about their knowledge by getting them to talk about and articulate what they know and understand. Such interactions can help students demonstrate their knowledge and applied experiences (where available). So staff have to identify what works for students in terms of development. In terms of critical analysis Sandie told of her approaches to addressing this.

Mannequins & metaphors

Sandie notes how she was supporting one student and used the idea of a mannequin as a metaphor. The mannequin is seen as a kind of basic structure from which to work (the essay question or assignment task). The student is the expert to design and dress the mannequin and the tools are their resources that they have available to them (e.g. library, books, journal articles and so on). Another example that Sandie gets students to consider are the UK TV shows Crimewatch and Sherlock Holmes. In this case one is highly descriptive of a series of events (Crimewatch), whereas the other one provides a highly critical and analytical set of events. In other words, the latter example is investigatory in nature as it takes a critical eye to detail while drawing or identifying links between evidence that is uncovered and discovered, and attempts to uncover further evidence that may not immediately be seen.In terms of academic writing, this can translate well for those who have seen the shows.Sandie also used the idea of getting a student to describe and evaluate an object in order to demonstrate to students that they actually do know how to analyze and evaluate. Sandie discussed how she showed students various objects of a similar nature (e.g. a chair) and had them describe/analyze which was best and why in order to instill the sense that students do know how to critically evaluate and provide such analysis. Sandie noted that students who lack confidence need to be aware that they can do this, and so using simple, real-world examples can help to illustrate this ability to students.

Further thoughts on criticality and reflective practices

Both Claire and Sandie noted that using metaphors and narrative can provide a path to criticality. These can get students talking and articulate their expertise in practice. Student talk can reveal reflective practice and decision making that they’ve undertaken. In other words, their narrative can translate into what they already know. This narrative process can also help students connect reflective professional practice with academic practice and academic assignments and vice versa (e.g. how to write reflectively vs how to write an academic essay, both of which are very different in terms of what and how discussion proceeds).

Opportunities & suggestions from the audience

Claire and Sandie noted that peer support can be one way of addressing students' needs in a personal way that can help alleviate pressure on resources. They noted that students are generally really good at critiquing others’ work and providing advice, so it is worthwhile using students’ own knowledge and experiences as a resource as it personalizes the interaction and also allows for feedback support in a different way. It can also help students to relax in the sense that they’ll soon understand that the questions, and that they have are shared questions. In short, others have had the same issues, others are experiencing the same or similar difficulties and it’s not ‘hard’ for that one student but actually for a wider range of people than they expect or know, which again can be refreshing in the sense that they might then be much more willing to collaborate with peers.

Comments & suggestions from the audience

One audience member asked whether this hierarchy of academic writing needs could be formalized, which garnered wide support among those present. I mentioned CeDAS's use of use of Connect2 as a means to address student 1:1 sign ups in such a way that it could get students to choose 3 areas of focus that they need help with in their essays. As one attendee noted, however, this presumes that the students actually know what they need or want help with, and so this would be something for me to consider during my own 1:1 sessions with students.Another attendee mentioned how workshops can be used as mini-focus groups in order to better understand what is needed by the students. The idea of reverse outlining was also mentioned. This is a method of outlining that has students first write up their essay and then read it to write an outline after the fact. This can help students who struggle to produce an outline, which might seem constraining given that it demands only main ideas, while allowing them to write freely initially and produce a sample of writing. Again, this approach can help students to achieve focus in a different way where writing an outline first might not work for them. A student prolific with ideas might find this approach particularly useful as it will allow them to write all of their ideas down, from which they can then trim and remove any unrelated ideas or ideas that don't fit neatly into their assignment.Another colleague noted how technology has allowed direct drafting which allows students (and staff!) to easily manipulate text and move around their ideas. This approach, however, has pitfalls. Students might copy/paste a piece of text and place it into a section where it will break the logical flow or perhaps won’t ‘fit’ due to the topic(s) being discussed within that section.

Talk 3: Are staff ready to answer the questions?

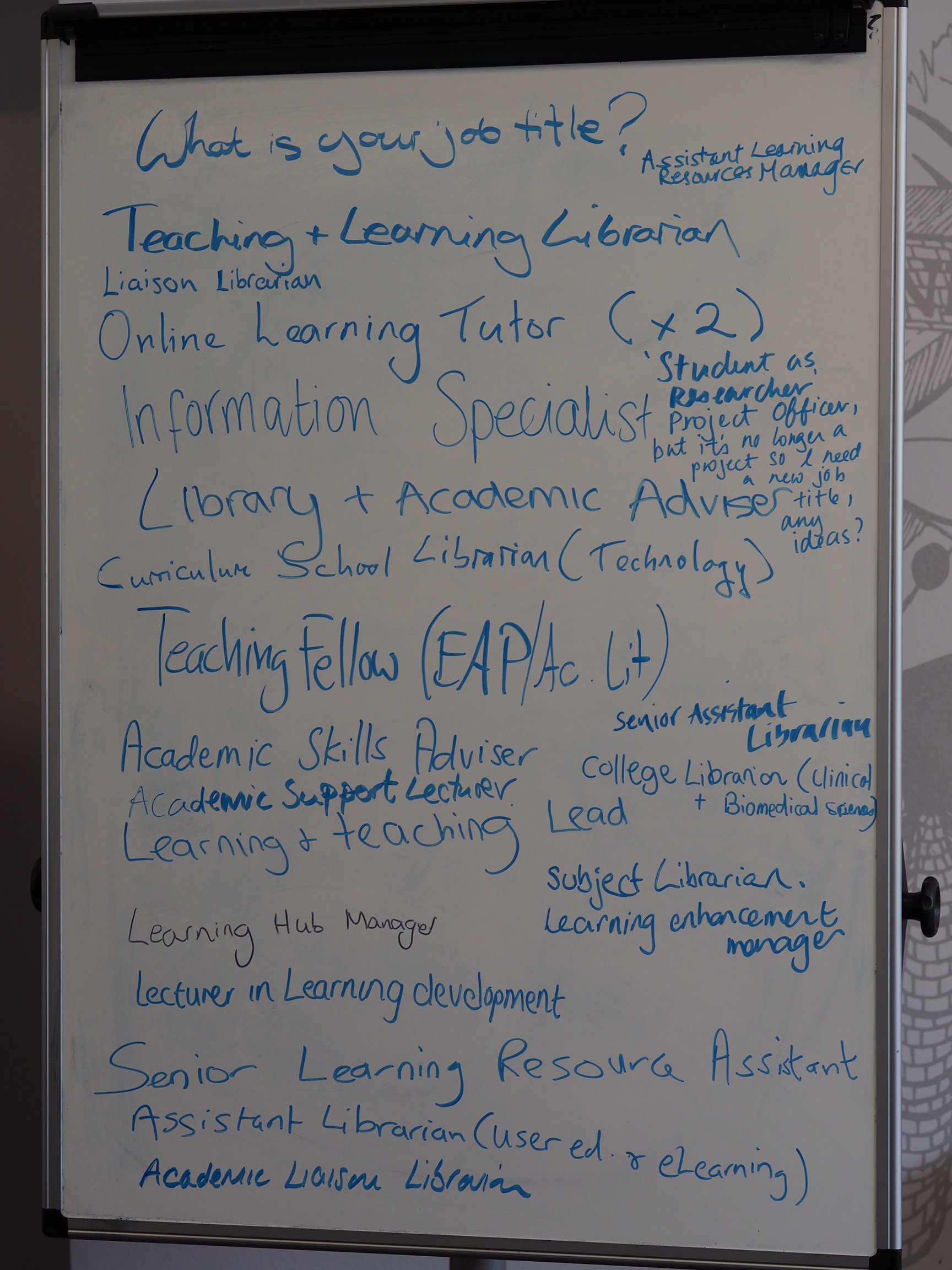

For me it was interesting to find out where staff were coming from as far as their backgrounds and roles, so I had asked one of the organizers if attendees could share this somehow. The results were interesting as they showed just how widely student support is cast and set within various universities: The last talk was delivered by academic librarian Emma Thompson, Learning and Teaching Lead, from the University of Liverpool. Emma told of how Liverpool has no central learning development department but it does have excellent support in some subjects but with lots of gaps in others.

The last talk was delivered by academic librarian Emma Thompson, Learning and Teaching Lead, from the University of Liverpool. Emma told of how Liverpool has no central learning development department but it does have excellent support in some subjects but with lots of gaps in others.

Emma stressed, however, that libraries are places where people ask all sorts of questions that go beyond the books themselves. She went on to discuss briefly how the library went on to developed a new program designed to address the needs of students. The library was receiving a lot of requests that were out of their remit and so they proceeded to investigate how to best deliver support by consulting other units that work with students. This allowed them to understand things from a student perspective, which is important to fully understand what their needs and demands are in terms of finding and getting developmental support and support more generally.

The program is called KnowHow and it consists of workshops blending learning development, digital literacies and information literacy. The stakeholders of this program included a variety of departments on campus, the library and...

- the Students' Union

- Careers

- Counselling Service

- Computing Services

- Educational Development

- ED helped with setting up writing support though initially the unit was for staff rather than students.

Emma spoke of a common question students often asked:

I keep losing marks for poor referencing - can you help?

In understanding how best to answer this commonly recurring question she first asked the following questions of her own role:

- Whose remit is it to address this particular issue?

- Whose territory is it? Does it matter?

One attendee noted that the policies of their university are very strict and that the definition of plagiarism and potential penalties in place could lead to the student’s removal if he/she makes even small mistakes such as a referencing error. This led to the following questions:

- How would you approach addressing this student's issue?

- What further questions might you ask?

- What kind of online resource or workshop might be suitable for this student?

In terms of a solution to the initial issue, following the narrative approach earlier mentioned, it was suggested that getting students to share what they’re trying to do and what they think needs to be done in relation to the feedback that they’ve received from lecturers might be a good way to initially approach the issue. The lecturer may note that referencing is an issue but the issue could be wider or narrower than the feedback suggests.

Communities of practice as a way to prepare staff to better answer queries

Emma discussed her experience of achieving an HEA recognition. She found the process of recognition helpful as it it evidence what she already did though at times she didn’t necessarily have the words to describe these with. This process also gave her some reassurance of some of her approaches to learning and teaching while allowing her to look critically at other practices (hers/others) and identifying the effectiveness or lack thereof of these. Emma did find it to be a challenging process but it allowed conversations to open up as she was able to learn from other professionals and ultimately build up a community of practice. Emma found the idea of communities of practice (Lave & Wenger 1991) as a very helpful way of learning and developing. It gives a frame around focusing what needs to be done in terms of a common concern or passion for something - in this case, developing her practice - by meeting, sharing and learning through one another how to do it better through this regular interaction. Through reflecting upon her experiences, Emma was able to understand that although some old/established UK universities do learning and teaching well and have clear strategies and policies in place, a lot of newer universities often have these strategies and policies in place and even have learning/teaching units/departments whose remit looks at how best to source and disseminate examples of good practices in learning and teaching whereas older universities may not have these in place. Indeed, some traditionally research intensive universities do not always hold learning and teaching to the same standard as research, however this will likely change given the introduction of the UK government’s Teaching Excellence Framework which will likely force all universities to re-evaluated learning and teaching in relation to the framework, identify gaps and develop these in order to meet the TEF’s aims.An attendee asks about potential difficulties with the HEA recognition process in terms of ‘fitting’ evidence within the realm of teaching for staff who may not explicitly teach (e.g. library staff, etc.) Emma noted that she has found that through joining a community of professionals she has been able to better understand how to approach achieving and evidencing HEA fellowship but also developing her learning and teaching. A community of practice is also about letting go of some stuff and being open-minded to the interactions while looking for common threads and identifying how best to address the learners’ needs in a learner centered way rather than service centered manner while considering on the core values espoused by a university in order to help them thrive.

Wrapping up: a discussion with Jennie Blake & Sam Aston

To wrap up, Jennie, a learning development manager, and Sam, a learning and teaching librarian, asked the audience to think about the talks and how we can apply what we’ve learned to our own contexts. They also left us with some questions to consider:

- How can this community of academic learning advisors and learning developers create resources that can be made available and useful for the wider group?

- What resources are available for supporting students?

- Where can we source these materials?

- What do the resources address?

- How are the resources licensed? (e.g. creative commons licensed materials)

They also left the audience with an invitation to reuse their own materials from My Learning Essentials, which are freely available on Jorum, and are Creative Commons licensed CC BY-NC.

First time (again)